THIS INSIDE UKRAINE STORY IS FROM Kyiv.

* All images and answers in the feature were provided by the WOW Woman, unless otherwise specified.

INSIDE UKRAINE SERIES: A SNAPSHOT, A DAY-IN-THE-LIFE, A GLIMPSE OF WHAT IT’S LIKE TO LIVE, RESIST, SURVIVE AND PERSEVERE IN A NATION UNDER ATTACK.

GLORY TO THE UKRAINIAN WOW WOMEN, who fight for freedom AND BRING UKRAINE CLOSER TO VICTORY.

A deeper understanding of russia’s war against Ukraine comes from the voices of those still living through it. My next WOW Woman is Haiane Avakian, a Ukrainian journalist from Bakhmut.

“Missile strikes first obliterated the roof, then the courtyard. We learned this from satellite images. Our family took nothing from the house except documents. Everything my parents had built was destroyed,” wrote Haiane.

Bakhmut no longer exists. The city was wiped out by relentless russian bombing. Haiane’s story is the story of tens of thousands of Ukrainians; from Mariupol to Kharkiv to Toretsk.

Forced to relocate her family to Kyiv, Haiane chose to act. She immediately co-founded Memorial, a national platform that records the names, faces, and biographies of Ukrainian children, civilians and defenders killed by russians since February 2022. Memorial is a powerful act of Ukrainian resistance, exposing the murders committed by the russian state. Haiane’s efforts preserve memory and truth, as russia attempts to erase both. So far, Haiane and her team have documented over 10,000 lives lost, building the largest known archive of Ukrainian deaths caused by the russian invasion.

In this interview, Haiane writes with dignity and defiance about what it means to lose your home, to carry grief with purpose, and to fight back by refusing to forget.

- Olga Shmaidenko, Founder of WOW Woman. Inside Ukraine is a WOW Woman series documenting the voices of Ukrainian women during the full-scale russian invasion. It bears witness to the human cost of war and to Ukrainian women’s refusal to be silenced.

Journalist, Preserver of National Memory, Kyiv

1. Name.

Haiane Avakian.

2. Where were you born and where do you live now? I read in your previous interview that your parents fled from Nagorno-Karabakh to Bakhmut. How are they doing now? Where have they found refuge?

I was born in Bakhmut, a small town in the Donetsk region in eastern Ukraine, in 1990. My parents are Armenians and refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh. They came to Ukraine when war and military actions began there. I lived my whole life in Bakhmut, but now, because of the full-scale invasion, I was forced to leave the city. The city has been completely destroyed by russia.

Currently, I live in Kyiv with my family – my 10-year-old son Tymofiy and my parents. It was very difficult for my parents to flee war for the second time and to start over. At their age, it's much harder. But we support each other.

We chose to stay in Ukraine, not to go abroad. So I continue to work. They help me raise my son.

3. What did you study and what is your current profession?

I’m a philologist of Ukrainian language and literature. I graduated from Donetsk National University in 2013 – six months before the city was occupied by russia and pro-russian militants. So yes, by education I’m a philologist, but for all of my adult life – since I was 17 – I’ve worked in journalism. I’m a journalist.

If we talk about my path in media, it began at a district newspaper. Then, when I was 21, we created the first city website in Bakhmut. Later, I joined the ABO Agency team, where we started developing local media across Ukraine, including in the East. Over five years, we managed to build a network of 52 sites in small towns.

But after the full-scale invasion, my work changed significantly. My current focus is the Memorial memory platform, which we founded in 2022, one month after russia attacked Ukraine.

So today, my field is both journalism and memory – working in the sphere of memorialization.

4. What did your typical day look like before the full-scale war? How did your life change after the invasion? Where were you, and how did you learn about the start of the russian full-scale aggression?

Before the full-scale invasion, I lived in Bakhmut. As I said, it’s a small town, so it was fairly comfortable – both to work remotely and to raise a child.

My workday usually began around 8 a.m. – with chats from local journalists across various regions of Ukraine. I helped them create editorial content, launch new sites, and restructure print newsrooms into online outlets. I also worked on the online magazine "Svoi," which told the stories of people from eastern Ukraine.

I did a lot of editorial work – collaborating with journalists and freelancers, commissioning stories. At one point, we even had reporters in Donetsk and Luhansk, who could more or less safely share information. So we published not only stories from government-controlled parts of Donetsk and Luhansk but also from occupied areas.

Of course, as for all Ukrainians, the full-scale invasion became a point of no return. My life changed drastically. I left Bakhmut on the very first day, February 24. We knew that journalists were a target for russians – they are kidnapped, tortured, killed, just like pro-Ukrainian activists. So I took my family and left immediately. I’ve never gone back.

I found out about the invasion around 5 a.m. – from a call from a colleague. She woke me up with the words: “He declared war. Putin attacked. Missiles are flying all over Ukraine.” It was terrifying. But by then I had already packed our things. I understood this was inevitable, that the threat was real. We had lived for eight years next to the occupation, along the contact line, and we knew well what russia was and what war was.

5. What did you decide to do next? It seems you took responsibility and acted.

Our first goal was to get to a relatively safe region. For us, that was Lviv oblast – a family there gave us shelter. We gathered part of our team – everyone who had managed to evacuate at that point. For several days, we were in a state of total uncertainty: what is happening, and what can we do that is meaningful and useful?

Parts of Luhansk were very quickly occupied. Some of our newsrooms also ended up under occupation, including in the north of Ukraine. Some teams were trapped and in danger. We realized that first, we had to help those we could still evacuate. We began coordinating evacuations, supporting colleagues who managed to get out. Unfortunately, not everyone could.

Another important step was changing the focus of our local media. We understood that our websites now had to talk about the full-scale war. It was already clear that Mariupol was under blockade, and we were trying to find out what was happening in the city. We felt that we had to document these events, tell the stories of eyewitnesses – people who had seen with their own eyes what russian soldiers were doing. That became our mission in the first months of the big war.

In March 2022, we launched the Memorial platform and began collecting the first stories of Ukrainians killed by russia. They were civilians, not soldiers. We wanted the dead not to remain nameless numbers in reports. We wanted to say their names. To show who exactly russia was killing:

Here we honour the memory of the children whose lives were taken by russia.

Here, we honour the memory of civilians who died as a result of the war that russia unleashed against Ukraine.

Here, we honour the memory of the defenders of Ukraine who died in the war.

Examples of Stories of Lives cut short by russian invaders, selected randomly from tens of thousands…

Daria Zadniprovska,

3 months

Daria was three months old when her life was taken by a Russian airstrike in Mariupol. She died on March 23, 2022 alongside her parents Viktoria and Oleksandr Zadniprovsky, under the rubble of their home at 19 Metalurhivska Street. On 15 May 2022, Oleksandr Zadniprovsky's father returned to the scene of the tragedy to retrieve and identify his relatives. “Oleksandr was holding his daughter in his arms. It was impossible to recognise her face,” said Anna Vakulenko, Daria's godmother. On 17 May 2022, the Zadniprovsky family was buried. Daria was laid to rest in the same grave as her mother. The coffins were closed. Daria Zadniprovsky is survived by her grandmother and grandfather.

Mykhailo Novikov, 8

The life of eight-year-old Mikhail Novikov was taken by russian shelling of Zaporizhzhia in the early hours of September 3, 2024. The enemy attacked the city, destroying the complex where the boy's family was staying. Mykhailo's mother was killed, and his sister and father were wounded.

Mykhailo Novikov was a student at the Progress Primary School in Zaporizhzhia. He was a good student and loved talking about travel and space. He was involved in sports and was interested in technology. Together with his classmates, he built structures out of construction sets and dreamed of building children's centres when he grew up.

"I remember it was first day of school and Mykhailo was standing in line with his mother, cheerful, positive, full of life and energy. He was talking to friends he hadn't seen for several months. He was a kind, bright, pure, little person who loved life, his friends and his family," said his teacher, Marina Chubir.

Mykhailo Novikov is survived by his father, sister and other relatives.

Valeria Simonnik, 17

Valeria Simonnik, 17, died on 27 June 2023 in Kramatorsk, Donetsk region. She worked in a restaurant that was hit by a rocket from the Russian army. That day, russian shelling of Kramatorsk and its surroundings, claimed the lives of 12 people.

Valeria Simonnik was born on August 23, 2005. She graduated from high school No. 31 in Kramatorsk. She enrolled in the Kramatorsk College of Technology and Design, where she was a student and class president. She worked as a waitress in a pizzeria. She was sociable, straightforward, and honest. She dreamed of visiting Lviv and buying her own car.

"Lerochka was the life of the party. She was the brightest person I knew. She was always smiling, and her smile melted hearts. She knew how to support others, was cheerful and fun. Sometimes it seemed to me that she was never sad... She loved loud music and dancing, beautiful landscapes, and warm summer nights. She loved strong hugs. And she admired the sunflower fields in summer as if they were some kind of miracle," said her friend Yevheniia about the deceased.

Valeria Simonnik is survived by her parents, younger brother and other relatives.

Andriy Ryhel, 17

Andriy Ryhel died in the middle of the night on 13 June 2023 in the city of Kryvyi Rih. Russian army missiles hit a bottled water warehouse, killing seven people who were working there. The youngest of them was Andriy Ryhel, 17 years old. About 25 civilians worked at the warehouse around the clock. Water was delivered to the communities in desperate need. That night, Andriy was working together with his friends Anton Babich and Vladislav Kuznetsov.

"Andriy was an active, cheerful, bright young man who was just starting to make plans for his life, breathing in every moment of it with a full chest", the Dzherelo Lyceum in Kryvyi Rih wrote about the deceased.

In total, the Russian army's missile attack on Kryvyi Rih that night claimed the lives of 12 people. Andriy and his friends were buried on 15 June 2023 in the village of Vilne. The deceased young man is survived by his mother, father and two brothers.

Inna Dikhtaenko, 25

Inna Dikhtaenko died on March 28 as a result of shelling in the village of Sviatopetrivske, Kyiv region. As a family doctor, Inna was helping to sort medicines at the time. Russian missiles hit the clinic where she was working. Inna died on the spot. Her colleague Vita Bilotska died in early June.

Inna Dikhtyarenko graduated from the Boyarsky Academic Lyceum She worked at the Primary Health Care Center in the village of Bilohorodka, Kyiv region, and then at the Sviatopetrivska Ambulatory Clinic No. 2. She lived in the village of Tarasivka.

Colleagues and friends say that Inna was passionate about her work: she never refused to help patients, even providing consultations and responding to calls outside of working hours.

Inna had not stopped working since the start of the full-scale invasion on February 24. She independently replenished the supplies of medicines needed by people in her community. On March 28, she went to get them once again.

"A bright, young woman, always smiling, friendly, polite, and incredibly beautiful. This girl had an unbreakable spirit. She loved people and believed in a bright future. Despite her young age, she was an excellent family doctor, saved many lives, and was always available," wrote Inna's friend Kateryna Lishchuk.

Inna is survived by her husband and father. On June 18, the President awarded the deceased family doctor the medal “For Saving Lives.” Sadova Street, 2, in the village of Tarasivka was renamed Inna Dikhtyarenko Street.

Serhii Savchuk, 28

Sergeant Serhii Savchuk, call-sign “Fillini”, was killed on April 7th, 2022 in Mariupol, Donetsk region. During his brave defense of the city against russian invaders, he sustained life-threatening injuries. The defender was 28 years old.

Serhiy was born in the village of Yavorivka in the Vinnytsia region. He graduated from Vinnytsia Agrarian University with a degree in management.

He participated in various sports, loved animals, especially large breeds of dogs. He was kind, sincere, reliable, and positive. He had a good sense of humor. He dreamed of having a big house and a family.

In 2019, he signed a contract with the National Guard of Ukraine. He served as an instructor in the 2nd division of the training company of the personnel training battalion. From the first days of the full-scale invasion, he defended Mariupol.

"Our son grew up honest, he didn't know how to lie. His eyes gave him away. He had many friends and knew how to be a friend. He loved his younger brother, who is 10 years younger than him. I see my son in my dreams. He jokes around, asks me not to worry and not to cry," his mom added.

Sergeant Serhiy Savchuk was posthumously awarded the Order of Courage, Third Class.

The defender is survived by his parents and younger brother.

Volodymyr Boichenko, 35

35-year-old locksmith and volunteer Volodymyr Boichenko was shot dead by Russians in Bucha, Kyiv region. Volodymyr lived in Gostomel. He was a locksmith by profession, but after February 24, 2022, he became a volunteer, delivering food and medicine to residents of Bucha, Irpin, and Gostomel. Together with his friends, he helped others evacuate.

"He called me every day and said he was alive and well, that everything was fine with him. He begged me to save kids. He said, ‘Run and escape now, because it's very scary here in Bucha. I'm looking for food, medicine, firewood and water. Whatever anyone needs. The guys and I are delivering it. You can't imagine how scary it is...’," said the victim's sister, Olena. She last spoke to her brother on March 8. Then the connection was cut.

In early April, his body was found in the basement of the Sunlight Children's Summer Camp in Bucha. The bodies of four of his acquaintances were also found there. According to the relatives of the deceased, on March 12, the men were driving people to evacuation buses, but the Russians stopped them and took them to the basement.

Volodymyr Boichenko is remembered as a very hard-working man. “My brother was, as they say, crazy about work. He understood electricity and could do it. He worked with wood and metal. He had golden hands...” said his sister Olena.

Dmitry Litvinov, 41

Dmytro Litvinov died on 8 July 2024 as a result of the russian shelling of the city of Kryvyi Rih. He was a chief specialist at the mining and processing plant which russians hit. Dmytro was at work when a rocket hit one of the buildings.

He knew every detail of his workshop. He was involved in transport modernisation.

His colleagues remember him as an experienced specialist, responsible and conscientious. He took on difficult problems and offered help to anyone who needed it. That was also the case on 8 July.

‘After the first russian strike, Dmytro was helping the wounded, but he himself was killed,’ said his colleague Andriy Skachkov.

Dmytro is survived by his wife, three daughters and other relatives.

Liudmyla Repina, 57

Lyudmyla Repina, 57, lived in Izium in a five-storey building at 2 Pershotravneva Street. On March 9th, 2022, Russians shelled this building with a tank and carried out air strikes. About 50 people died in the rubble. Among the victims were Lyudmyla, her husband, son and mother.

Lyudmila worked in the education department and was an engineer by training. She studied at the Kharkiv Polytechnic Institute. While still a student, she met her husband Yuri. For many friends and acquaintances, the Repins were a model of family relations. Yuriy would pick Lyudmila up from work, and they would walk around the city hand in hand, spending all their time together.

Lyudmila is remembered as a good hostess. She often treated her colleagues from the education department to her homemade pastries. She dreamed of grandchildren and renovating her own home.

‘Lyudmila always came to the rescue. Friends and colleagues knew they could rely on her. She would give her last penny to help,’ recalls her colleague Marina Shevlyakova.

Lyudmila Repina is survived by her cousin and nephew.

Zhanna Rostovskaya, 62

Zhanna Rostovskaya worked as a postal worker in Mariupol. She was killed in a russian airstrike on Mariupol on March 14th, 2025. The attack also killed her daughter Tetyana and her 9-year-old granddaughter Varvara.

On 14 March, heavy shelling began. One of the shells hit the house. The roof caught fire. Ilya and Tetyana, along with their daughters Varvara and Karina and their grandmother Zhanna, grabbed their belongings and ran out into the street. They wanted to get to the nearest shelter. But the children ran out without shoes, so Ilya rushed back home to get them. At that moment, he heard the sound of an aircraft. He shouted, ‘Get down!’ Then there was an air strike. The man grabbed the shoes and ran back to his family. His wife Tetyana was killed instantly. His younger granddaughter Varya was fatally wounded and died in Hospital No. 3. Zhanna was wounded in the chest and lived for another two minutes, recalls her son-in-law Ilya. He says, “I apologised to her and said I was going to save the girls.”

Zhanna Oleksandrivna was born and lived in Mariupol. She worked as a postwoman and had recently retired. Her friends and colleagues respected and honoured her. Zhanna is remembered as a kind-hearted person who adored her children and grandchildren.

Zhanna Alexandrovna and her granddaughter Varya were born on the same day, 7 February. They also died on the same day, 14 March. They are buried in the Starokrymsky Cemetery. Zhanna's daughter Tatyana is also buried there.

Zhanna Rostovskaya is survived by two granddaughters, her younger daughter and son-in-law.

Ihor Shynkaruk, 63

Senior Lieutenant Ihor Shynkaruk, call-sign “Father”, died on April 15, 2022, in Mariupol, Donetsk Oblast. He was fatally wounded while performing a combat mission during the russian advance on the Azovstal steelworks plant in Mariupol. He served in the Azov Special Forces Regiment. Igor was 63 years old.

Born in the town of Chornyi Ostriv in the Khmelnytskyi region, Ihor studied at the mechanical faculty of the Riga Institute of Civil Aviation Engineers.

Later, he moved with his family to the Kyiv region and transferred to the Kyiv Institute of Civil Aviation Engineers. He served in the army. He worked at various enterprises. He held the position of chief engineer for medical gas supply networks.

With the start of the full-scale invasion, he voluntarily joined the defense of Ukraine. He served in the Azov Special Forces Regiment (military unit A3449). He took part in a secret operation of the Main Intelligence Directorate—a helicopter flight to the besieged city of Mariupol to help his comrades.

“My husband loved to read, was interested in computer science, and loved to travel,” said his wife, Raisa.

The soldier was buried in the village of Tarasivka in the Kyiv region.

Ihor is survived by his wife and daughter.

A cube in honor of the soldier was installed on the Walk of Fame in the city of Boyarka, Kyiv region.

Lydia Yefremenko, 75

On March 8, 2022, Lydia Yefremenko turned 75. The next day, she was killed by shelling of a house on Pershotravna Street, 2, in Izyum. In January 2023, this street was renamed Memory Street. On March 9, 2022, about 50 people were killed in house No. 2 here.

Lydia Yefremenko and her neighbors were hiding in the basement of the building, but enemy shelling destroyed two entrances and all five floors collapsed and buried the shelter.

Lydia was retired. Before that, she had worked as a saleswoman for 35 years. Flowers were her true passion. They bloomed on every windowsill in her home. Lydia also planted a flower bed outside her apartment windows.

Her neighbor Tetyana says, “Lydia tried to make her flower garden bright and blooming as long as possible. After the tragedy, the flower bed is completely gone—parts of the building collapsed on it.” Lydia loved to read and had her own library. In recent years, she constantly reread the Bible.

She gave the Holy Scriptures to her granddaughter Aliona. This Bible and a few photos are all that remain of her grandmother's belongings.

Friends remember Lydia Yefremenko as a caring and loving grandmother: she adored and raised first her children, then her grandchildren and great-grandchildren. She kept the belongings of her 22-year-old grandson, Serhiy Goncharenko, who was killed in the ATO. He was one of 49 paratroopers who died on June 14, 2014, when the Russians shot down an Il-76 over Luhansk. Now, a few meters from her grandson, Lidiya is buried next to her husband.

Lidia Yefremenko is survived by her daughter, granddaughter, and two great-grandchildren.

That was our first mission – to name the names, to give faces to those being erased. In the first year of the full-scale invasion, especially in the first months, we were completely mobilized. We saw where we could be useful. We managed to preserve and even expand our team to have the resources to keep going.

And most importantly – we made our choice. We decided to stay in Ukraine. We decided to be useful – not at the front, but by countering russian propaganda through documenting and recording russia’s war crimes.

6. What are your strengths and superpowers?

I think my strengths are multitasking and quick adaptability. Despite everything I’ve been through in the past ten years, I remain resilient. I go through difficult circumstances in a way that I’m not ashamed of my actions or decisions.

Another one of my strengths is strategic thinking. Over the past few years, I’ve been developing strategies for media and civil society organizations. And it’s really inspiring when you see a strategy turn into real results – when a team works in sync and achieves exactly what was planned.

7. What actions are you continuing to take to support Ukraine and the Ukrainian people?

Right now, most of my work time is dedicated to working with memory. In fact, along with my colleagues – like other civil society organizations in this field – we are laying the foundation for how Ukrainians will remember this war. Will politicians be able to rewrite the history we’re living through in this historic moment? Will russia be able to manipulate the facts?

My professional work is directly connected to ensuring that memory becomes an inseparable part of both the wartime and postwar context. That we preserve the truth, give names to the dead, document the experience.

“Memory is action.” The slogan of Memorial’s crowdfunding campaign was printed on cardboard signs to support the continuation of the team’s work. The campaign launched in October 2024 and raised over 4 million UAH.

A Memory Table at one of the 800 restaurants and cafes across Ukraine that joined the action in honor of fallen defenders.

The tables were reserved for an entire day “for the bravest among us” and included sunflowers as symbols of remembrance.

Presentation of the “Donate to Remember” campaign for Ukrainian businesses.

Screening of the film “118 Victories,” which tells the story of the aftermath of the russian missile strike on a residential building in Dnipro on January 14, 2023. The attack killed 46 people, including seven children. Over 200 people attended the screening in Dnipro, including relatives of the victims and survivors of the attack.

Award ceremony at Ukraine Pravda 2024, where Memorial was recognized as the best social project of the year.

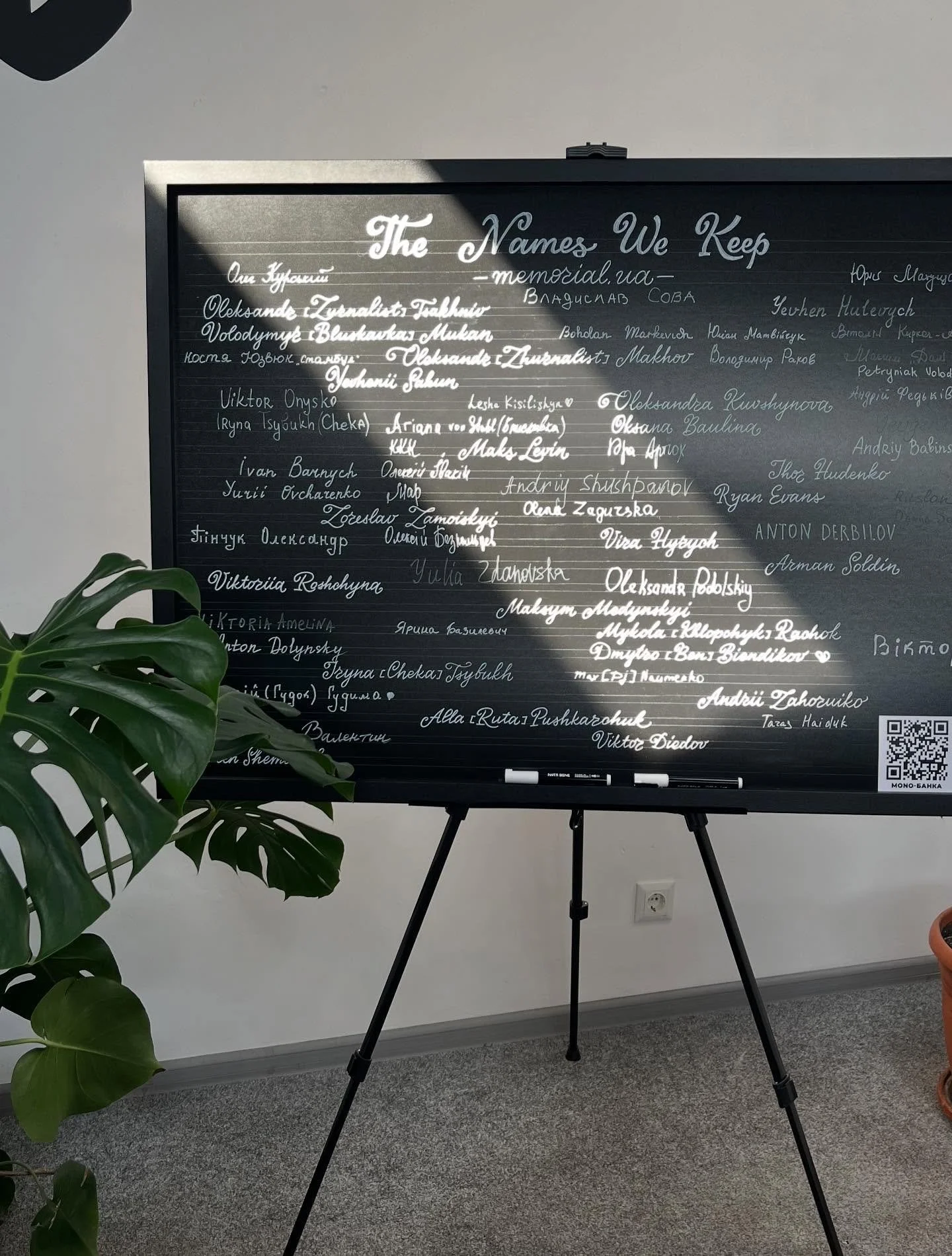

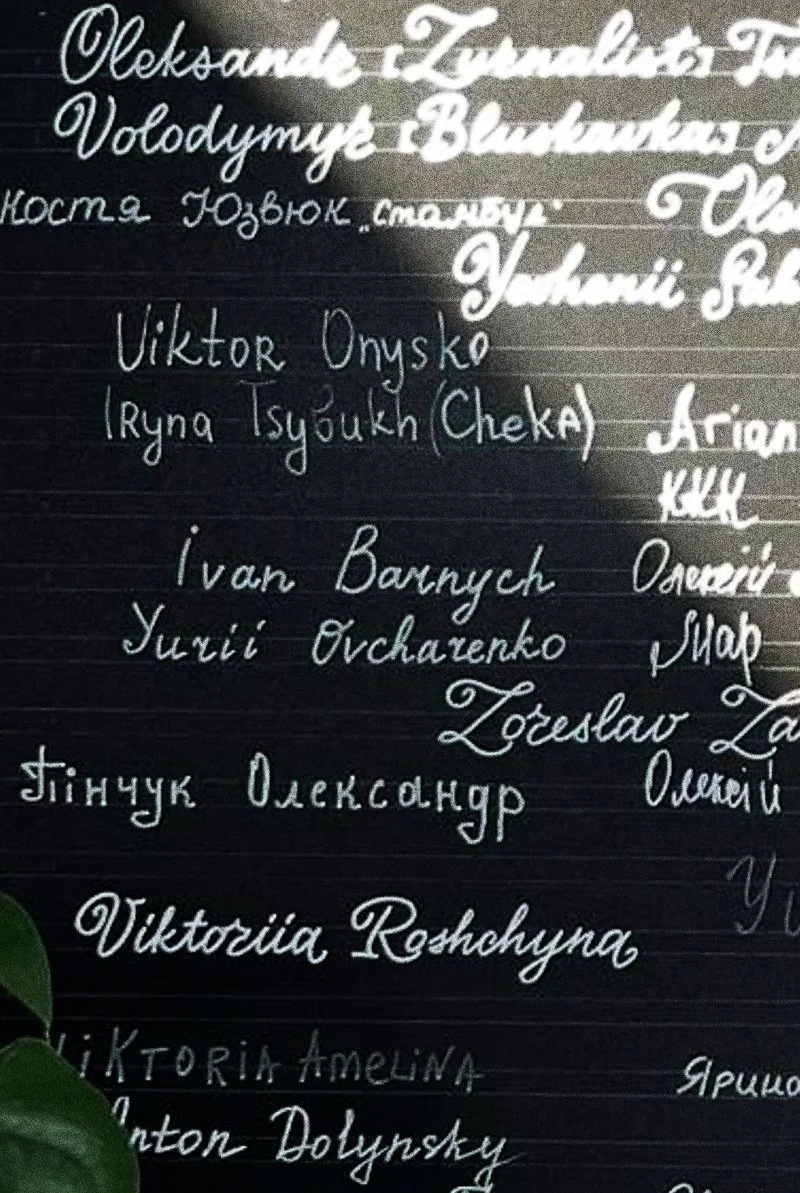

The Names We Keep memorial wall listing the names of fallen Ukrainian journalists—both civilian and military. Created at the Lviv Media Forum 2025, where participants could add the names of their killed colleagues.

Memory videos have been broadcast on Kyiv’s largest screen every evening for over a year and a half. This is memory in the public space, and the queue for broadcast currently includes over 200 stories.

Like many Ukrainians, supporting the Armed Forces is a constant, ongoing action. We often say that memory is action, and that means not only honoring the fallen but also helping the living. Donations to the military, sharing fundraisers, jars of support – that’s what I and those around me do every day.

It’s also important to me that I can publicly share my thoughts about the war, support for Ukraine, and express these ideas in media and among my colleagues. That too is a form of action – deliberate, daily, and deeply personal.

8. How do you take care of yourself? Is it even possible to remain mentally stable during war? What helps you pull yourself together?

Honestly, there are a few things that help me hold on.

First – my family and my son. I work a lot, but I genuinely enjoy spending time with Tymofiy. Especially when we get to travel – sometimes we manage to leave the country, even just briefly. Travel helps you see that a world without war still exists. A world where you can live without fear. And it reminds us what we’re fighting for – for peace, long-lasting, just, and our own.

Even work trips often have a therapeutic effect.

In daily life, plants help me a lot. I have many in my office, and I love cut flowers – they give the sense that life continues, even during war. Despite shelling, despite loss – spring comes, trees bloom, apples ripen. That’s an important reminder: life goes on, and we must do everything we can to make it peaceful.

Of course, there are periods of exhaustion. Because of intense work, the news, the feeling of how long this war has gone on – it’s already the eleventh year. But I don’t allow myself to sink into despair. I believe that endurance, caring for yourself and your loved ones – that too is a form of resistance.

Books also help me a lot. After evacuating from Bakhmut, I was only able to take a few favorite books. One of them was George Orwell’s 1984. That book feels very symbolic to me now.

I’m slowly rebuilding my library, buying new books – mostly nonfiction about the war in Ukraine and modern history.

9. You’ve written countless pages in memory of Ukrainians who defended their country and were killed by russians. Have you ever had to stop and scream from pain or anger? How do you gather yourself again and face a new day?

I work on the Memorial memory platform, which now holds the largest archive of stories about Ukrainians who were killed. It’s over 10,000 stories, published not only on our website but also by our media partners. A team of more than 10 people works on it – journalists, editors, video producers. We create both written memory pieces and video documentaries.

One project that’s particularly important to me is my own initiative called Your Favorite Dish. In it, mothers of fallen defenders prepare meals their sons and daughters loved most. It’s a very quiet, sincere kind of confession. Through simple homemade food, we speak the language of love for those we’ve lost. It’s our attempt to talk about memory not only through facts and dates but also through warmth, tenderness, everyday life.

The most difficult day of the war for me was probably July 28–29, 2022 – the day russia killed over 50 Ukrainian prisoners of war in Olenivka. They were defenders of Mariupol. They had been promised safety – international organizations gave formal guarantees that they would return home through a prisoner exchange after leaving Azovstal. But russia killed them – brutally, in the middle of the night, blowing up Barrack No. 200 where they were being held.

That day I felt absolute despair and rage. We tried to respond – posted materials on social media – but it was hard even to comprehend what had happened. The next evening, families of the Olenivka prisoners gathered on Sofiyska Square in Kyiv. It was extremely painful – to look them in the eyes, to grasp the scale of that crime. I want very much to believe that those responsible – for this and all of russia’s war crimes – will be punished.

Another very difficult part of our work is the stories of children that we collect and publish. In them, you feel most sharply the sense of a life interrupted. These children loved, dreamed, had a future. They could have become someone important. But they didn’t. Because they were killed.

10. Please tell me about your hometown - Bakhmut. What are your warmest memories there? What was your city like, and how will you remember it?

In the first year after evacuation, after the most brutal fighting for the city, after seeing how russia literally turned Bakhmut into ruins, it became incredibly difficult for me to speak about it.

This city – my city – is the place where I was born. And it’s painful to understand how many Ukrainian defenders died there trying to hold it. I wrote one article about Bakhmut for The Atlantic – it was a virtual tour of a city that no longer exists. But since then, I almost never speak about it out loud. It’s too painful.

I sincerely hope that those who are reading these words never experience what it’s like to lose the place where you grew up, and to know that you will probably never be able to return.

Unfortunately, I don’t have optimistic scenarios for the restoration of Bakhmut or the region as a whole. Because I know the scale of the destruction. I’ve seen what russia has done – simply erased towns from the face of the earth, turned them into concrete wastelands, mined and dangerous.

Still, Bakhmut returns to me – often through Google Photos. They remind me daily: here’s four years ago, five, ten. And every time, it’s Bakhmut. I remember the day we went down into the salt mines – 300 meters underground, a unique place that used to attract tourists from all over the world. Or I think of our house. My parents’ house, which they built over many years with their own hands. There was a tall cherry tree in the yard. And the apricots were incredibly sweet.

And no one could have imagined that even such simple memories – of fruit, of trees, of home – would one day become a source of pain.

Bakhmut Before.

Bakhmut now.

click on image for the source.

“Memories of the city that once was”, by Haiane Avakian for The Atlantic.

“Sometimes, I stare for hours at new photos of ruins published in local chat groups. I’m looking for the city I remember: I’ve walked this street hundreds of times on my way to school; my classmate lived in that building; my dentist worked in the neighboring one, where I had an appointment on February 24, 2022, that I never made. When I identify the neighborhood, I feel relief: I haven’t forgotten everything. My town is imprinted in me.” - Haiane Avakian

11. Do you feel the war has changed you? In what ways? Have you surprised yourself – how you held on, stayed strong, found inspiration in unexpected places? In your view of your country, humanity, or the world – what shifted for you?

The war has changed all of us. First and foremost, we’ve understood again: freedom and democracy are values worth fighting for. We’ve also seen how strong we can be when we act together, when we unite. Yes, I’ve changed too. I have more gray hair from stress. But I’ve also realized that I’m capable not just of surviving, but of supporting others, of being a source of strength for my loved ones. This situation showed me something important: when faced with danger, my instinct isn’t to freeze or flee - it’s to act. To keep working. To keep fighting. Even when it’s frightening and painful.

12. What do you want the world to know about Ukrainians at this moment in time?

I want the world to see and support our determined struggle for survival - the existential war we are fighting against russia. This is not just a war over territory – it’s a war for the right to exist, for freedom, for dignity, for life itself.

I want the world to understand: if Ukraine falls, russia will not stop. This is not an exaggeration. It is a serious threat to the whole of Europe, to global security, to the future of the democratic world.

I truly believe the world can and must learn from Ukraine. Learn courage, solidarity, endurance, and how to preserve humanity in inhuman conditions. Today, Ukraine is a country that leads by example.

13. What about Ukrainian women? Which WOW-women inspire you?

I don’t have idols among foreign politicians or famous journalists. To me, every Ukrainian woman is example of a WOW Woman. After heavy shellings, after losses, after great pain – we continue to live. We continue to fight. It’s deeply moving. I admire women who didn’t break but turned their pain into action. The family of Iryna Tsybukh, a medic from Kharkiv region, is organizing a memorial festival in her honor. Maria Hrabar, widow of fallen defender Illia Hrabar, launched the national campaign “Stand in Memory.” Yulia and Solomiia – relatives of a man killed in Olenivka – keep his memory alive. The family of Bohdana “Kosmos,” a paramedic killed by russia, continues to raise funds for the Armed Forces and preserve her name among the living.

I could go on endlessly. These are women who sleep in bomb shelters and still make breakfast for their children in the morning. Who help them with schoolwork despite the war. Who protect their loved ones, support their communities, work, volunteer, fight.

And most of all, I admire the courage of Ukrainian women soldiers - like Olena Ryzh, a combat medic and assault trooper, or Valeriia Subotina – a former prisoner of war, a Mariupol defender who returned to military service after her release from russian captivity. Each one of them does something crucial for our resilience. For our victory.

14. What place or activity makes you happiest?

Maybe I would name the forest near our home in Kyiv as my happy place. We rent an apartment nearby, and this forest is a nature reserve. It’s a very calm, peaceful place, right next to the noisy city. I love walking there, photographing the plants and trees we see with my son. I probably wouldn’t call it “the happiest place” in my life – it’s too hard to think in those terms right now. But it is definitely a place of balance. A place that gives me peace, quiet, presence, and helps me relax – even just a little.

15. What will be the first thing you do when Ukraine wins? What do you dream of for yourself and your family after the war ends?

That’s a difficult question – what I’ll do when Ukraine wins. Difficult because it’s hard to imagine life without war. But I want very much to learn to imagine it again. I think on that day, I’ll genuinely smile and genuinely cry – from joy, from relief, from everything we’ve lived through. It will be a tear of victory and of pain at the same time.

For my family, I dream of a home. I don’t even know if it will be the same home we lost. But I want to have our own place again, where we feel safe.

And I just want to live to see that day – peace, victory. Because right now, we live under threat nearly every day: drones, missiles, losses. On the Memorial platform, there are more and more stories not only about fallen soldiers but about civilians as well.

16. In your view, how are russians as a people different from Ukrainians? (many in the West, unfortunately, still need to be reminded and told about this.) Did we know about these differences before the full-scale invasion? Were we in denial?

Ukraine is not russia. And the Ukrainian people differ from the russian people first and foremost in our desire for freedom. For us, the core value is human life. And that is the most important thing.

Our enemy demonstrates the exact opposite. russia shows that human life has no value to it. This is clear in everything – from its military tactics to its propaganda. They still repeat the Soviet-era slogan: “women will give birth to more.” This way of thinking is inhumane. It has nothing to do with the civilized world, with democracy, with dignity, with basic sense.

17. Do you feel that people who left Ukraine during the 2022 wave, or Ukrainians who have lived abroad for years, have any responsibility to their homeland?

Of course, both those who left and those who stayed have a responsibility to their country. Ukrainian citizenship gives us not only rights, but obligations. Right now, as a society, we are going through a very difficult test – a test of maturity, of unity, of our ability to stand together at a critical moment in history.

Another hard test lies ahead – the stage of internal understanding. Between those who had to flee, those who stayed, and those who lived through occupation. It won’t be easy, but without it, we won’t be able to rebuild the country as a whole.

I see that part of the Ukrainian diaspora abroad is very proactive. They go to rallies, organize fundraisers, send humanitarian aid, and fight the information war. They speak about Ukraine in the countries where they now live. And this advocacy is incredibly important for us.

I also want to say: those who took their children abroad carry a responsibility not only to the state, but to their children. Many of them did this out of necessity, as refugees, saving their children from mortal danger. And that responsibility is deep, human, and understandable. It cannot be dismissed. It needs to be acknowledged – on both sides.

18. You also lead a media agency. How do you divide your time between that work and your work for the Memorial Memory Platform? What other projects is ABO Agency planning?

For the past three years, I worked as Director of Product Development at ABO Media Development Agency, where I helped build various journalism products. One of those was the Memorial Memory Platform. But over the last year, Memorial has grown so much that it’s no longer just one of many projects – it has become my main professional and personal priority.

Today, the majority of my efforts are focused specifically on developing this platform – on strategic development, public presentation, and working with the team.

19. Where can others find information about you and your work? (Website, social media, etc.)

Website: https://memorial.ua/

Instagram: @victims_of_russia

Facebook: facebook.com/uaspeaker

ЦЯ ІСТОРІЯ ДЛЯ «INSIDE UKRAINE» З КИЄВА.

* Всі фотографії та відповіді в матеріалі були надані WOW Woman, якщо вказано інакше.

СЕРІЯ INSIDE UKRAINE/ВСЕРЕДИНІ УКРАЇНИ: МОМЕНТАЛЬНИЙ ЗНІМОК, ОДИН ДЕНЬ З ЖИТТЯ, ПОГЛЯД НА ТЕ, ЯК ЦЕ - ЖИТИ, ЧИНИТИ ОПІР, ВИЖИВАТИ І НЕ ЗДАВАТИСЯ В КРАЇНІ, ЯКА ПЕРЕБУВАЄ ПІД ЗАГРОЗОЮ.

СЛАВА українським WOW-жінкам, ЯКІ ПІДТРИМУЮТЬ СВОЮ УКРАЇНУ І НАБЛИЖАЮТЬ КРАЇНУ ДО ПЕРЕМОГИ.

Глибше розуміння війни росії проти України можна отримати з вуст тих, хто все ще переживає її. Моя наступна WOW-Жінка - Гаяне Авакян, українська журналістка з Бахмута. "Ракетні удари спочатку знищили дах, а потім подвір'я. Ми дізналися про це зі супутникових знімків. Наша сім'я нічого не забрала з будинку, окрім документів. Все, що побудували мої батьки, було зруйновано", написала Гаяне. Бахмута більше не існує. Місто було стерте з лиця землі безперервними російськими бомбардуваннями. Історія Гаяне - це історія десятків тисяч українців: від Маріуполя до Харкова і Торецька.

Змушена перевезти свою сім'ю до Києва, Гаяне вирішила діяти. Вона одразу ж стала співзасновницею «Меморіалу» - національної платформи, яка фіксує імена, обличчя та біографії українських дітей, цивільних та захисників, вбитих росіянами з лютого 2022 року. «Меморіал» є потужним актом українського спротиву, який викриває вбивства, скоєні російською державою. Зусилля Гаяне зберігають пам'ять і правду, в той час як росія намагається стерти і те, і інше.

Наразі Гаяне та її команда задокументували понад 10 000 втрачених життів, створивши найбільший з відомих архівів смертей українців, спричинених російським вторгненням. У цьому інтерв'ю Гаяне з гідністю та викликом пише про те, що означає втратити свій дім, нести горе цілеспрямовано та давати відсіч, відмовляючись забувати.

- Ольга Шмайденко, засновниця WOW Woman. Inside Ukraine — це серія WOW Woman, яка документує голоси українських жінок під час повномасштабного російського вторгнення. Серія є свідченням людських втрат війни та відмови українських жінок замовчувати.

Журналістка, Хранителька Національної Пам'яті, Київ

1. Імʼя

Гаяне Авакян (Haiane Avakian)

2. Де ви народилися і де ви зараз живете? Я читала у вашому минулому інтерв'ю, що ваші батьки виїхали з Нагірного Карабаху до Бахмута. Як вони? Як вони тримаються зараз і де вони знайшли притулок?

Я народилася у місті Бахмут, невеликому містечку на Донеччині на сході України у 1990 році. Мої батьки – вірмени і біженці з Нагірного Карабаху. Вони приїхали в Україну, коли там почалася також війна, військові дії. І все своє життя я жила у Бахмуті, а зараз через повномасштабне вторгнення вимушено виїхала з міста. Місто наразі повністю знищене росією.

Наразі я разом з родиною, своїм 10-річним сином Тимофієм і батьками ми живемо в Києві. Батьки дуже складно пережили необхідність вдруге тікати від війни, необхідність починати все з початку. В їхньому віці це набагато складнішеі. Але ми підтримуємо один одного. Наш вибір був залишитися в Україні, а не їхати за кордон. Тому я продовжую працювати. Вони допомагають мені з вихованням мого сина.

3. На кого навчались та за якою професією працюєте зараз?

За фахом я — філолог української мови та літератури. Закінчила Донецький національний університет, встигла завершити його у 2013 році — за пів року до окупації міста росіянами та проросійськими бойовиками.

Власне, так, за освітою я філолог, але все своє свідоме життя — з 17 років — я працюю в журналістиці. Я — журналістка.

Якщо говорити про мій шлях у медіа, то спочатку це була районна газета. Потім, коли мені було 21 рік, ми створили перший у Бахмуті онлайн-сайт про місто. А коли я приєдналася до команди агенції «АБО», ми почали займатися розвитком локальних медіа по всій Україні, зокрема й на Сході.

За понад п’ять років нам вдалося створити мережу з 52 сайтів у локальних, невеликих містечках.

Але після повномасштабного вторгнення моя робота сильно змінилася. Зараз фокус моєї уваги — це платформа памʼяті «Меморіал», яку ми заснували у 2022 році, за місяць після того, як Росія напала на Україну.

Тому сьогодні моя сфера діяльності — це і журналістика, і робота з памʼяттю, робота в сфері меморіалізації.

4. Як виглядав ваш звичайний день до повномасштабного та як змінилася ваше життя після вторгнення в Україну? Де ви були і як дізналися/відчули початок російського наступу?

Моє життя до повномасштабного вторгнення проходило в Бахмуті. Як я вже казала, це невелике містечко, тож там було досить комфортно — і працювати (я працювала дистанційно), і виховувати сина.

Зазвичай мій робочий день починався вже о восьмій ранку — з перших чатів з локальними журналістами з різних регіонів України. Я допомагала їм створювати редакційний контент, запускати нові сайти, переформатовуватися з газетних редакцій у онлайн-редакції. Також я займалася розвитком онлайн-журналу «Свої», який розповідав історії людей зі Сходу України.

Я дуже багато працювала як редакторка: співпрацювала з журналістами, фрилансерами, замовляла їм тексти. Колись у нас були репортери навіть у Донецьку та Луганську, які могли більш-менш безпечно передавати інформацію. Тому ми публікували не тільки історії з підконтрольних територій Донеччини та Луганщини, але й з окупованих.

Звісно, як і для всіх українців, повномасштабне вторгнення стало точкою неповернення. Моє життя кардинально змінилося. Я виїхала з Бахмута вже в перший день, 24 лютого. Ми усвідомлювали, що журналісти — це одна з цілей для росіян: їх викрадають, катують, вбивають, як і проукраїнських активістів. Тому я забрала родину і виїхала одразу. І більше до свого міста вже не поверталася.

Про початок вторгнення я дізналася близько п’ятої ранку — від дзвінка колеги. Вона розбудила мене словами: «Він оголосив нам війну. Путін напав. Ракети летять по всій Україні». Це було моторошно. Але на той момент у мене вже були зібрані речі. Я розуміла, що це неминуче, що загроза реальна. Ми вісім років жили поруч з окупацією, на лінії зіткнення, і добре знали, що таке Росія і що таке війна.

5. Що ви вирішили робити далі? Здається, ви берете на себе відповідальність і дієте. Чи це так, і що ви вирішили робити?

Першою нашою справою було дістатися до більш-менш безпечного регіону. Для нас це була Львівщина — нас прийняла родина в одному з будинків. Ми зібрали там частину нашої команди — всіх, хто зміг евакуюватися на той момент. Кілька днів ми перебували в абсолютному нерозумінні: що відбувається і що ми можемо зробити важливого й корисного в цій ситуації.

Частина Луганщини дуже швидко опинилася в окупації. Деякі з наших редакцій теж потрапили під окупацію, зокрема і на півночі України. Частина команд залишилася в небезпеці, відрізаними. Ми зрозуміли: передусім ми маємо допомогти тим, кого ще можемо евакуювати. Почалася координація — допомога з евакуацією, підтримка наших колег, яким вдалося виїхати. На жаль, не всі змогли.

Інше важливе рішення — змінити фокус наших локальних медіа. Ми зрозуміли, що тепер на наших сайтах ми маємо говорити про повномасштабну війну. Уже тоді було зрозуміло, що Маріуполь у блокаді, і ми намагалися зʼясувати, що відбувається в місті. Ми відчули, що маємо фіксувати ці події, розповідати історії очевидців — людей, які бачили на власні очі, на що здатні російські військові. Це і стало нашою місією в перші місяці великої війни.

У березні 2022 року ми запустили платформу памʼяті «Меморіал». Ми почали збирати перші історії людей, вбитих Росією. Тоді це були цивільні, не військові. Ми хотіли, щоб загиблі не залишалися безіменними цифрами в зведеннях. Ми хотіли називати імена. Показувати, кого саме вбиває Росія.

Це й була наша перша місія — називати імена, давати обличчя тим, кого знищують. І справді, у перший рік повномасштабного вторгнення, особливо в перші місяці, ми були максимально мобілізовані. Ми зрозуміли, де можемо бути корисними. Нам вдалося зберегти й навіть розширити команду, щоб мати ресурс і далі працювати.

А найголовніше — ми зробили свій вибір. Ми вирішили залишитися в Україні. Ми вирішили бути корисними — не на фронті, але у протидії російській пропаганді через документування і фіксацію воєнних злочинів Росії.

6. Які, на вашу думку, ваші сильні сторони та надздібності?

Мені здається, що моя сильна сторона — це мультизадачність і вміння швидко адаптуватися. Попри всі випробування, які випали на мою долю за останні десять років, я залишаюся стійкою. Я проходила крізь складні обставини так, щоб не соромитися своїх рішень і дій.

Ще одна моя сильна сторона — це стратегічне мислення. Протягом останніх років я займалася розробкою стратегій для медіа та громадських організацій. І це справді надихає, коли бачиш, як стратегія перетворюється на реальні результати: коли команда працює злагоджено, і вдається досягти саме того, що було заплановано.

7. Які конкретні дії продовжуєте робити, щоб допомогти Україні та українському народу?

Зараз більшість мого робочого часу присвячена саме роботі з пам’яттю. Фактично ми разом із колегами — так само як і інші громадські організації, що працюють у цій сфері — закладаємо фундамент того, як українці пам’ятатимуть цю війну. Чи зможуть політики переписати історію, в якій ми живемо просто зараз, у цей великий історичний момент? Чи зможе Росія маніпулювати фактами?

Моя професійна діяльність безпосередньо пов’язана з тим, щоби пам’ять стала невіддільною частиною і воєнного, і повоєнного контексту. Щоб зберегти правду, надати імена загиблим, зафіксувати досвід.

Як і для багатьох українців, підтримка ЗСУ — це постійна, перманентна дія. Ми часто говоримо, що памʼять — це дія, і це означає не лише вшанування полеглих, а й допомогу живим. Донати на ЗСУ, поширення зборів, баночки підтримки — це те, що роблю я і моє оточення щодня.

Також для мене важливо, що я можу публічно транслювати свої думки про війну, підтримку України, доносити ці сенси через медіа і в колі колег. Це теж моя форма дії — усвідомлена, щоденна і дуже особиста.

8. Як ви дбаєте про себе? Чи можна взагалі залишатися морально стабільним в умовах війни? Що саме допомагає вам збирати себе докупи?

Насправді є кілька речей, які допомагають мені триматися.

По-перше — це моя родина і мій син. Я багато працюю, але мені справді цікаво проводити час із Тимофієм. Особливо це стосується подорожей — нам іноді вдається виїжджати за кордон, бодай ненадовго. Подорожі допомагають побачити, що існує світ без війни. Світ, у якому можна жити без страху. І це нагадує, за що ми боремося: за мир — тривалий, справедливий, наш.

Хоча подорожі часто бувають і робочими, але навіть у них є терапевтичний ефект.

У повсякденному житті мені дуже допомагають рослини. В офісі в мене багато вазонів, і я люблю зрізані квіти — вони дають відчуття, що життя триває попри війну. Попри обстріли, попри втрати — приходить весна, цвітуть дерева, дозрівають яблука. І це дуже важливе нагадування: життя продовжується, і ми повинні зробити все, щоб воно стало мирним.

Звісно, бувають періоди виснаження. Через інтенсивну роботу, через новини, через відчуття довготривалості цієї війни — вже одинадцятий рік. Але я не дозволяю собі йти в зневіру. Вірю, що витримка, турбота про себе й близьких — це теж наша форма опору.

Також, насправді, мені дуже допомагають книги. Після евакуації з Бахмута, на жаль, я змогла забрати лише кілька улюблених видань. Одна з них — це «1984» Джорджа Орвелла. Ця книга для мене дуже символічна зараз.

Я поступово відновлюю свою бібліотеку, купую нові книжки. Переважно це нонфікшн — видання, що стосуються війни в Україні, сучасної історії.

9. Ви написали величезну кількість сторінок, присвячених пам'яті українців, які захищали свою країну і були вбиті росіянами. Чи доводилося вам зупинятися і просто кричати від болю і гніву? Як після цього взяти себе в руки і почати новий день?

Я працюю на платформі памʼяті «Меморіал», яка наразі зібрала найбільший архів історій про загиблих українців. Це вже понад 10 000 історій, опублікованих не лише на нашому сайті, а й у партнерських медіа. Над ними працює команда з понад 10 людей — журналістів, редакторів, відеопродакшену. Ми створюємо як текстові історії памʼяті, так і відео, документальні фільми.

Окремо для мене важливим є мій авторський проєкт — «Твоя улюблена страва». У ньому мами загиблих захисників готують страви, які найбільше любили їхні сини й доньки. Це дуже тиха й щира сповідь. Через просту домашню їжу ми говоримо мовою любові до тих, кого втратили. Це наша спроба говорити про пам’ять не лише через факти й дати, а через тепло, ніжність, щоденність.

Найважчим днем війни для мене, мабуть, став 28–29 липня 2022 року — день, коли Росія вбила понад 50 українських військовополонених в Оленівці. Це були захисники Маріуполя. Їм гарантували безпеку — міжнародні організації давали офіційні гарантії, що після виходу з «Азовсталі» вони повернуться додому через обмін. Але Росія вбила їх — жорстоко, вночі, підірвавши барак №200, у якому вони перебували.

У той день я відчувала абсолютний розпач і злість. Ми намагалися якось реагувати — публікували матеріали в соцмережах, але було важко навіть просто усвідомити, що це сталося. Наступного вечора на Софійській площі в Києві зібралися рідні полонених з Оленівки. Це було надзвичайно болісно — дивитися їм в очі, розуміти масштаб цього злочину. Дуже хочеться вірити, що винні в цьому й усіх інших воєнних злочинах Росії — будуть покарані.

Ще один дуже складний аспект нашої роботи — це історії дітей, які ми збираємо та публікуємо. В них найгостріше відчувається обірваність життя. Ці діти любили, мріяли, мали майбутнє. Вони могли б стати кимось важливим. Але вони не стали. Бо були вбиті.

10. Напишіть, будь ласка, про своє рідне місто Бахмут, які найтепліші спогади про нього? Яким було ваше місто і яким ви його назавжди запам'ятаєте?

У перший рік після евакуації, після найжорсткіших боїв за місто, після того, як я побачила, як Росія буквально перетворила Бахмут на руїни, мені стало неймовірно важко говорити про нього.

Це місто — моє місто. Місце, де я народилася. І мені боляче усвідомлювати, скільки українських захисників загинуло там, намагаючись утримати його. Я написала один текст про Бахмут для журналу The Atlantic — це була віртуальна екскурсія містом, якого більше немає. Але з того часу майже не говорю про нього вголос. Це надто боляче.

Я щиро сподіваюся, що ті, хто зараз читає ці слова, ніколи не зрозуміють, що це — втратити місце, де ти виріс, і знати, що ти, ймовірно, більше ніколи не зможеш туди повернутися. У мене, на жаль, немає оптимістичних сценаріїв для відновлення Бахмута чи цього регіону загалом. Бо я знаю масштаби знищення. Я бачила, що зробила Росія — просто стерла міста з лиця землі, перетворила їх на бетонні пустелі, заміновані й небезпечні.

Та все одно Бахмут повертається до мене — зокрема через Google Photos. Вони щодня нагадують: ось чотири роки тому, ось п’ять, ось десять. І щоразу це світлини з Бахмута. Наприклад, з того дня, коли ми спускалися в соляні шахти — 300 метрів під землею, унікальне місце, куди приїжджали туристи з усього світу.

Або я згадую свій дім. Дім моїх батьків, який вони будували роками, своїми руками. У дворі росла висока черешня. І були дуже смачні абрикоси. І ніхто не знав, що навіть така проста пам’ять — про фрукти, про дерева, про дім — стане колись болем.

11. Чи відчуваєте, що війна змінила вас? Яким чином? Чи здивувались ви самій собі (як ви тримались, залишалися сильними, знаходили натхнення в несподіваних джерелах тощо), у своїй країні, у своїх уявленнях про людяність, у своєму ставленні до світу? Що стало для вас прозрінням?

Війна дуже змінила нас усіх.

Перш за все, ми ще раз усвідомили: свобода і демократія — це цінності, за які варто боротися. Ми також побачили, наскільки сильними можемо бути, коли діємо разом, коли об’єднуємо зусилля.

Так, я справді змінилася. У мені з’явилося більше сивого волосся через стреси. Але водночас я зрозуміла, що здатна не лише триматися, а й підтримувати інших, бути опорою для близьких.

Ця ситуація показала мені важливу річ: у момент небезпеки мій внутрішній сценарій — не втеча, не завмирання, а дія. Продовжувати працювати, продовжувати боротися, навіть коли страшно і боляче.

12. Що ви хочете, щоб світ знав про українців у цей момент часу?

Я би хотіла, щоб світ побачив і підтримав нашу наполегливу боротьбу за існування — екзистенційну війну, яку ми ведемо проти Росії. Це не просто війна за територію — це війна за право бути, за свободу, за гідність, за життя.

Хочу, щоб світ усвідомив: якщо Україна впаде — Росія не зупиниться. Це не перебільшення. Це — серйозна загроза для всієї Європи, для глобальної безпеки, для майбутнього демократичного світу.

А ще я щиро вірю, що світ може і має вчитися в України. Вчитися мужності, солідарності, витримці, здатності зберігати людяність у нелюдських умовах. Україна сьогодні — це країна-приклад.

13. Про українських жінок? Які WOW-жінки вас надихають?

У мене немає кумирів серед політиків чи відомих журналістів за кордоном. Я вважаю, що сьогодні приклад для мене — це кожна українська жінка.

Після важких обстрілів, після втрат, після великого болю — ми продовжуємо жити. Ми продовжуємо боротися. Це вражає.

Мене захоплюють жінки, які не зламалися, а перетворили свій біль на дію. Родина Ірини Цибух, госпітальєрки з Харківщини, влаштовує фестиваль її пам’яті. Марія Грабар, дружина полеглого захисника Іллі Грабара, запустила національну акцію «Стій у пам’яті». Юлія та Соломія — родина вбитого в Оленівці — тримають памʼять про нього живою. Богдана «Космос», парамедикиня, яку вбила Росія — її близькі постійно збирають кошти на підтримку ЗСУ і зберігають її ім’я серед живих.

Я можу продовжувати цей список без кінця. Це жінки, які ночують в укриттях, а зранку готують сніданки своїм дітям. Які допомагають їм вчитися попри війну. Які бережуть своїх близьких, підтримують свої громади, працюють, волонтерять, воюють.

А найбільше я захоплююся сміливістю українських військовослужбовиць. Як от Олена Риж,бойова медикиня і штурмовичка, Валерія Суботіна — колишня військовополонена, захисниця Маріуполя, яка знову повернулися до війська. Кожна з них робить надважливе для нашої стійкості. Для нашої перемоги.

14. Яке місце або заняття робить вас найщасливішою?

Можливо, я би назвала ліс поряд з нашим будинком у Києві своїм щасливим місцем. Ми зараз орендуємо квартиру поруч, і цей ліс — заповідник. Дуже спокійне, затишне місце, зовсім поряд із шумним містом.

Я люблю там гуляти, фотографувати рослини й дерева, які ми зустрічаємо з сином. Напевно, я не можу назвати цей ліс «найщасливішим місцем» у своєму житті — зараз надто складно думати в таких категоріях. Але це точно місце рівноваги. Місце, яке дарує мені спокій, тишу, присутність, допомагає трохи розслабитися.

15. Що ви зробите в першу чергу, коли Україна переможе? Про що ви мрієте для себе та своєї родини після закінчення війни?

Це складне питання — що я зроблю, коли Україна переможе. Складне, бо важко уявити життя без війни. Але дуже хочеться навчитися знову його уявляти.

Мені здається, що в той день я щиро радітиму і щиро плакатиму — від радості, від полегшення, від усього, що з нами сталося. Це буде сльоза перемоги й болю водночас.

Для своєї родини я мрію про дім. Навіть не знаю, чи це буде той самий дім, який ми втратили. Але хочеться знову мати своє місце на землі, де буде безпечно. І хочеться просто дожити до цього дня — до миру, до перемоги. Бо зараз ми живемо під загрозою майже щодня: дрони, ракети, втрати. На платформі «Меморіал» з’являється все більше історій не лише про загиблих військових, а й про цивільних.

16. Чим, на Вашу думку, росіяни як народ відрізняються від українців (багатьом на заході, на жаль, доводиться про це нагадувать і розповідати)? Чи знали ми про ці відмінності до повномасштабного конфлікту? Чи були в стані заперечення?

Україна — не Росія. І український народ відрізняється від російського передусім своїм прагненням до свободи. Для нас базова цінність — людське життя. І саме це — найголовніше.

Наш ворог показує прямо протилежне. Росія демонструє, що для неї людське життя не має жодної вартості. Це добре видно у всьому: від воєнної тактики до пропаганди. У них досі живий радянський наратив: «баби ще нарожають». Це мислення — антигуманне. Воно не має нічого спільного з цивілізованим світом, з демократією, з гідністю, зі здоровим глуздом.

17. Чи відчуваєте ви, що люди, які виїхали з України під час хвилі виїзду у 2022 році, або ті українці, які вже роками живуть за кордоном, чи мають вони якусь відповідальність перед батьківщиною?

Звісно, і ті, хто поїхав, і ті, хто залишився, мають відповідальність перед своєю країною. Українське громадянство дає нам не лише права, а й обовʼязки. І зараз ми, як суспільство, проходимо дуже складний іспит — на зрілість, на єдність, на здатність триматися разом у критичний момент історії.

Попереду на нас чекає ще одне важке випробування — етап внутрішнього порозуміння. Між тими, хто був змушений виїхати, тими, хто залишився, і тими, хто пережив окупацію. Це буде непросто, але без цього ми не зможемо відновити країну як єдине ціле.

Я бачу, що частина української спільноти за кордоном дуже проактивна. Вони виходять на мітинги, проводять збори, передають гуманітарну допомогу, ведуть інформаційну боротьбу. Вони говорять про Україну в тих країнах, де зараз перебувають. І ця адвокація для нас надзвичайно важлива.

Також я хочу сказати: ті, хто вивіз дітей за кордон, — вони несуть відповідальність не лише перед державою, а й перед своїми дітьми. Багато з них зробили цей крок вимушено, як біженці, рятуючи дітей від смертельної небезпеки. І ця відповідальність — глибока, людська, зрозуміла. Нею не можна знехтувати, її треба визнати з обох боків.

18. Ви також керуєте медіа-агенцією. Як ви розподіляєте свій час між цією роботою та роботою для Платформи пам'яті «Меморіал»? Які ще проекти планує ABO Agency?

Останні три роки я працювала як директорка з розвитку продуктів Агенції медійного росту Або, де допомагала розвивати різні журналістські продукти. Одним з них була платформа памʼяті «Меморіал».

Але за останній рік «Меморіал» виріс настільки, що став для мене не просто одним із проєктів, а головним професійним і життєвим пріоритетом. Сьогодні більшість моїх зусиль зосереджені саме на розвитку цієї платформи: на стратегічному розвитку, публічному представленні, роботі з командою.

19. Де інші можуть знайти інформацію про вас/вашу діяльність? (посилання на вебсайт, сторінки в соцмережах тощо)