THIS INSIDE UKRAINian Heart interview IS FROM St Andrews, Scotland, United Kingdom

* All images and answers in the feature were provided by the WOW Woman, unless otherwise specified.

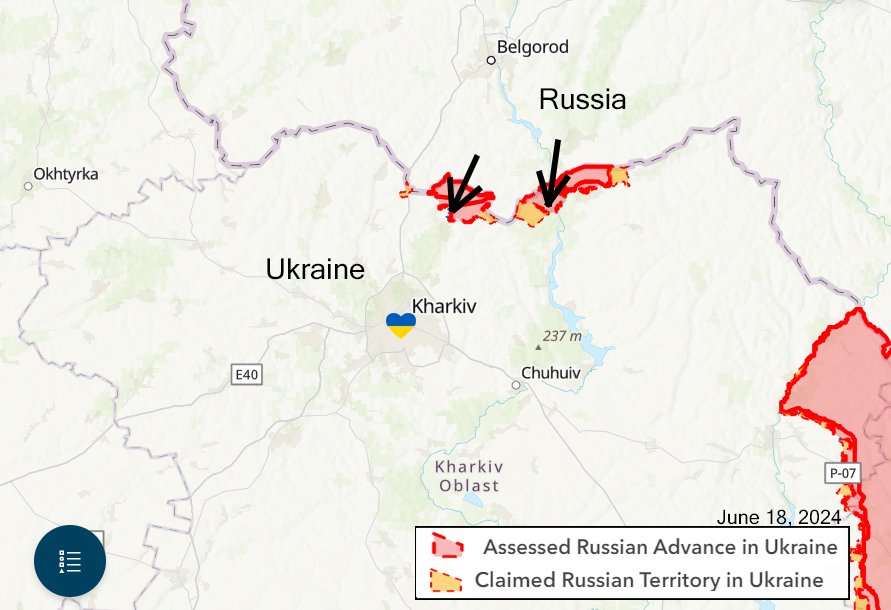

I have always wanted to visit Ukraine’s intellectual and educational center, beautiful Kharkiv. Often described as the city of students, universities, and science, Kharkiv today is a symbol of endurance under constant russian attacks. So close to the russian border and withstanding relentless strikes, Kharkiv residents embody a unique kind of resilience. When I see posts from there, I pay close attention. Kharkiv’s proximity to russia is only 20 miles (30 kilometers). That means there is no time for air raid alerts to reach people’s phones before russian missiles strike. This reality makes me even more determined to amplify voices from Kharkiv. I dream of visiting one day and meeting the incredible women I have been fortunate to feature on WOW Woman.

Viktoriia Grivina is one of them. An anthropologist and writer from Kharkiv, she is completing her PhD at the University of St Andrews in Scotland. When the full-scale russian invasion began, her academic focus shifted from studying post-industrial transformations in Kharkiv to exploring how its culture adapts and survives during war. From this turning point came two books, "Kharkiv: A War City" and "Kharkiv is a Dream", both created with love and respect for her hometown. Through her writing, Viktoriia captures the soul of Kharkiv, its architecture, resilience, humor, and pain, and invites readers to reflect on what it means to live, not merely survive, amid destruction. Her work offers a glimpse into Ukraine’s cultural memory and explores Ukrainian empathy and wit.

- Olga Shmaidenko, Founder of WOW Woman

Anthropologist, PhD Candidate, Writer

1. Name.

Viktoriia Grivina.

2. In which city were you born?

Kharkiv, Ukraine.

Image of Kharkiv sources: Wikipedia & Institute for the Study of War.

3. What is your profession, and has it changed compared to what you did before? What does your typical day look like?

I am an anthropologist and a PhD candidate at the University of St Andrews (Scotland). My doctoral studies began at the end of 2021, and in January 2022 I came from Kharkiv to Scotland.

After the full-scale invasion, I had to change my research topic, from studying the deindustrialization of Kharkiv and the transformation of factories into cultural centers, to researching how the city’s culture adapts during wartime. Because of this significant shift in focus, I had to extend my project by a year, and now I have about four months left until completion.

My days are spent writing and editing my manuscript. I usually work around 8-9 hours a day and read in my free time.

4. What have you done in your life that you are most proud of?

In 2024–25, I wrote two books about Kharkiv. One of them, Kharkiv - A War City, is a collection of essays and stories published since 2022 in various outlets and literary journals in the US, UK, Austria, and Vietnam. I dedicated this book to my parents and my great-grandmother Oryna, who lived through a terrible yet remarkable life in 20th-century Kharkiv region.

The second one, Kharkiv is a Dream, is a collaborative project with two amazing women: artist and architect Vasylisa Shchogolieva and anthropologist Hjordis Clemensen. Together, we explore the city’s cultural activism and aesthetics from 2013 to 2023. This project was born out of deep love for Kharkiv and great respect for my colleagues. We have become a true support system for each other during these challenging years of full-scale war.

“This collection of essays offers a glimpse into life in and around Kharkiv during the first two years of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. A Kharkiv native, Vikoriia Grivina reflects on living in a city where days are full of poetry readings and gallery openings, while nights are saturated with air raids and explosions.”

“When the war hit Kharkiv in 2022, the urban space transformed at a scale impossible for its inhabitants and artistic community to process. As it turns out, the urban space of Kharkiv was difficult to process long before the impact of drones and missiles. Kharkiv has been transforming for centuries, collecting monuments and memories from the ebbs and flows of history. The authors zoom in on three events over the past decade that reflect how different actors used the cityscape of Kharkiv to make sense of and shape their context.”

5. Advice for other women? For Ukrainian women abroad?

Don’t be afraid to go beyond stereotypes. Live where you feel comfortable. Sometimes, comfort can even be found where bombs are falling, it happens. There’s a difference between living and merely surviving. I always ask myself: am I truly living now, am I happy, or am I just surviving? Our enemy wants us not to live, not to have a full life. We must remember that.

I believe Ukrainian women are deeply vital; they have an extraordinary ability to live with joy even in the darkest times. That vitality helps us believe in victory and take steps toward it.

6. What or who inspires you?

I’m inspired by architecture, by stars over a summer field, by people, courage, and the talent to create something new. I’m inspired by kind acts and empathy. By the glass blocks of abandoned brick factories, the ruins of the Budy porcelain plant. By “kushuri,” wild nature, and the Donets River. And of course, by beautiful men too.

7. What (at least) three qualities do you love most in yourself, and why? What are your superpowers?

I love maps and have a good sense of direction. I can respond sharply and humorously to someone’s aggressive words. I laugh loudly and dance at home.

8. How do you feel about challenges? What drives you forward?

I love challenges, deadlines, and constructive criticism. I can work hard and productively. Optimism and kind words about my work inspire me most.

9. Where can others find you or your work (websites, Facebook, blogs, etc.)?

instagram: @vika4good

facebook: viktoria.grivina

medium: viktoriagrivina.medium.com

x: brams884

bluesky: brams884

Where were you when the russian invasion began? Did you believe it was possible that russia would attack major Ukrainian cities and start a full-scale war?

I was in St Andrews, Scotland. I didn’t believe it. I was absurdly certain that nothing would happen.

What did you feel on the day the war began? Where did you go, and what was your plan, as far as you remember?

I was in shock for several weeks; my hands were shaking. My plan was to bring my parents to Scotland and then return to Kharkiv myself. I really wanted to go back, but I assessed my situation and realized that in those first months, I would be more useful abroad, raising funds and lobbying for support.

How are your family and friends? How often do you speak with them?

As my father once wrote, “everything is fine (except for the war, of course).” It’s hard to say “everything is fine.”

Some of my friends and defenders have been killed.

What specific actions (big or small) have you taken and continue to take to help Ukraine and its people?

In the first months, we organized many collections with other students, finding helmets, body armor, and other gear for friends serving in the territorial defense. Later, I focused on cultural events. I organized a seminar series, Spotlight on Ukraine, dedicated to Ukraine’s energy sector during the war. Then a series of Ukrainian literature reading seminars.

Currently, I’ve set up a literary and art residency in my apartment in Kharkiv called The Quiet Centre. The residents take part in online seminars for international student audiences, Dispatches from the Quiet Centre.

Photos above: (1) Windows of the “City Kafe 1654” on Constitution Square. It was bombed and covered up by wooden boards, with artwork from a local children art school AzaNiziMaza. Cafe has since reopened, (2) My office at St Andrews, Scotland, (3) My parents’ kitchen window in Kharkiv, 2022, (4) Easter sale for Ukrainian Society at St Andrews University, Scotland, 2025. На знімках: (1) Вікна «Міське кафе 1654» на площі Конституції в Харкові. Кафе було бомбардовано і закрито дерев'яними дошками, на яких були розміщені роботи місцевої дитячої художньої школи AzaNiziMaza. Кафе вже знову відкрилося, (2) Мій офіс у Сент-Ендрюсі, Шотландія, (3) Вікно кухні моїх батьків у Харкові, 2022 рік, (4) Великодній розпродаж для Українського товариства в університеті Сент-Ендрюс, Шотландія, 2025 рік.

Do you feel the war has changed you? How? Did anything about yourself surprise you since the beginning of the war, how you coped with challenges, stayed strong, or found inspiration in unexpected places? What became a revelation for you?

Of course, it has changed me. Like Kharkiv, I have become less naive, angrier. My anger grows every day, but it is positive energy; it inspires me to work, to achieve more in this life. I was not surprised, but I was very pleased by the humanity and courage of the people of Kharkiv and all Ukrainians in the first months of the full-scale invasion. That spirit was incredibly inspiring; it made it impossible to just lie down and do nothing.

An epiphany for me were the cynicism and unseriousness of Western political systems as well as maturity and wisdom that emerged in so many Ukrainians.

In your opinion, how do russians differ from Ukrainians? Do you want justice for Ukrainians? Do you think it’s possible and how would you want it to happen?

It’s hard for me to speak about russians. I haven’t interacted with many. I’ve noticed a certain arrogance toward others, but I don’t have enough data to generalize.

Ukrainians often underestimate their abilities. We value a certain chaos that accompanies all democratic processes. We know how to laugh, not cruelly, not to humiliate. russian jokes almost always contain insult or humiliation of someone. We can laugh at ourselves.

I believe justice must be the true outcome of this war. Regaining territory isn’t enough; the russian people must come to a deep understanding of the horrific crime they’ve committed and the reasons that led to it.

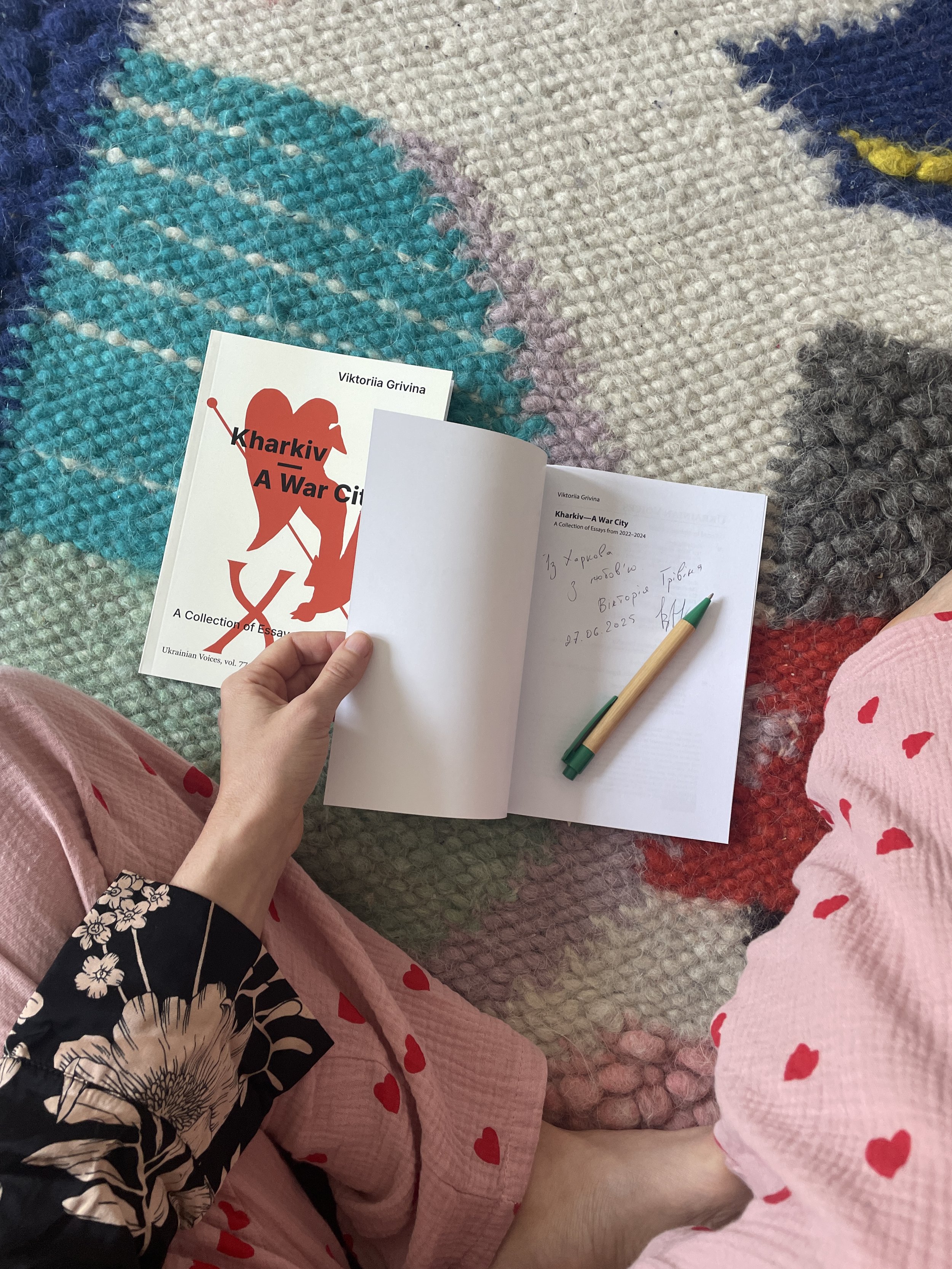

Photos above: (1) Wasting summer raspberries from a Deoccupation Shop (started by Meriam Yol and selling produ'cts from de-occupied villages of Kharkiv) on a Theatre Lane in downtown Kharkiv, (2) Derzhprom, the first modernist skyscraper in Eastern Europe, after russian missile attack. (3) Signing my first book, “Kharkiv, A War City”, in my apartment in Kharkiv. (4) Spring 2024, showing Sharivka Mansion in the Kharkiv region to the writers from Kyiv and Luhansk. На знімках: (1) Літня малина з магазину «Лавка деокупації» (заснованого Меріам Йол, який продає продукти з деокупованих сіл Харківської області) на Театральній вулиці в центрі Харкова, (2) Держпром, перший модерністський хмарочос у Східній Європі, після російського ракетного удару. (3) Підписання моєї першої книги «Харків, Місто Війни» у моїй квартирі в Харкові. (4) Весна 2024 року, показ Шарівського маєтку в Харківській області письменникам з Києва та Луганська.

What would you like the world to know, realize, or appreciate about Ukrainians, especially Ukrainian women?

That Ukraine is a vast country, the largest democracy (though not a perfect one) in Europe. Its expanses, its diverse landscapes, and its local cultures are still waiting to be fully discovered by the world.

What is it like to live abroad now and stay connected with your family and loved ones back home? Can you describe it for those who cannot feel it personally?

Living abroad is harder for me than living in Ukraine. The shelling feels even more painful from afar, the fear for my loved ones intensifies. In Kharkiv, we are all in the same boat, all equally vulnerable to russian bombs. Abroad, I am just a person who happened to survive, living among millions who don’t have a war.

Ukrainians living abroad, whether for one year or twenty, do they have a responsibility toward their homeland in these difficult times (to act, to fundraise, even to do small things)?

I think being part of the global Ukrainian community is a conscious choice. It can’t be imposed, it must come naturally. The diaspora preserved countless treasures of Ukrainian culture during Soviet times, doing everything possible to keep it alive.

Today, anyone can learn Ukrainian, become part of our culture, volunteer, or research our history. These people are also Ukrainians now, part of our shared community.

What will you do first when Ukraine wins? What do you dream of for yourself and your family after the war ends?

For my family, I dream of a nice little house at our dacha in Pechenihy, and to denounce the developers who put up fences along the banks of the reservoir.

After the war, I will go to Arabat Spit in Crimea and to Dzharylgach island in Kherson region. I will sit on Demerdzhi in Crimea and remember 2013, everything that happened to us.

Then I’ll finish writing the book about it.

Це інтерв'ю «Усередині українського серця» з Сент-Ендрюс, Шотландія, Велика Британія

* Всі зображення та відповіді в матеріалі були надані WOW Woman.

Я завжди хотіла завітати до інтелектуального та освітнього центру України, прекрасного Харкова. Місто, яке часто називають містом студентів, університетів та науки, сьогодні є символом витривалості під постійними російськими атаками. Мешканці Харкова, які знаходяться так близько до російського кордону і витримують постійні удари, демонструють унікальну стійкість. Коли я бачу дописи звідти, я приділяю їм особливу увагу. Харків знаходиться всього в 20 милях (30 кілометрах) від росії. Це означає, що до того, як російські ракети вдарять, у людей немає часу, щоб отримати повідомлення про повітряну тривогу на своїх телефонах. Ця реальність робить мене ще більш рішучою поширювати голоси з Харкова. Я мрію одного дня відвідати це місто і зустрітися з неймовірними жінками, яких я мала щастя представити на WOW Woman.

Вікторія Грівіна - одна з них. Антропологиня і письменниця з Харкова, вона закінчує докторську дисертацію в Університеті Сент-Ендрюс у Шотландії. Коли почалася повномасштабна агресія, Вікторія переключилася з дослідження постіндустріальних трансформацій у Харкові на дослідження того, як культура міста адаптується і виживає під час війни. Цей поворотний момент дав початок двом книгам, «Харків: місто війни» і «Харків — це мрія», обидві написані з любов'ю і повагою до рідного міста. У своїх творах Вікторія відображає душу Харкова, його архітектуру, стійкість, гумор і біль, а також запрошує читачів замислитися над тим, що означає жити, а не просто виживати, серед руйнувань. Її роботи дають змогу зазирнути в культурну пам'ять України та досліджують українську емпатію та дотепність.

- Ольга Шмайденко, засновниця WOW Woman

1. Ім'я.

Вікторія Грівіна.

2. В якому місті ви народилися?

Харків.

3. Яка ваша професія і чи змінилася вона порівняно з тим, що ви робили раніше? Як проходить ваш звичайний день?

Я антропологиня, аспірантка університету Сент-Ендрюс (Шотландія). Моя аспірантура почалась в кінці 2021 року, і в січні 2022 я приїхала з Харкова до Шотландії.

Після повномасштабного вторгнення довелось змінити тему дослідження, з деіндустріалізаціі Харкова і перетворення заводів на культурні центри, на дослідження адаптації культури міста підчас війни. Через цю доволі помітну зміну фокусу я була змушена продовжити проєкт на рік, і наразі маю ще 4 місяці до його завершення.

Мій день проходить за написанням та редактурою рукопису. Працюю вдень близько 8-9 годин, у вільний час читаю.

4. Що ви зробили у своєму житті, чим найбільше пишаєтеся?

У 2024-25 роках я написала дві книги про Харків. Одна з них Kharkiv - A War City - збірка есеів і оповідань, що публікувалися з 2022 року у різних виданнях та літературних журналах в США, Британії, Австрії, В'єтнамі. Цю книгу я присвятила моїм батькам, а також прабабусі Орині, що прожила страшне і надзвичайне життя на Харківщині 20 століття.

Друга - Kharkiv is a Dream - проєкт-колаборація із двома фантастичними людьми, мисткинею і архітекторкою Василісою Щоголевою та антропологинею Хьордіс Клеменсен. Разом ми досліджуємо культурний активізм та естетику міста 2013-2023 років. Цей проєкт було створено у великій любові до Харкова і повазі до моїх колежанок. Ми стали справжньою системою підтримки одна для одної у складні роки повномасштабної війни.

5. Порада для інших жінок? Для українських жінок за кордоном?

Не боятись виходити за межі стереотипів. Жити там, де вам комфортно. Іноді комфортніше там, де розриваються бомби, що ж, буває і так. Є різниця між життям і виживанням. І я завжди запитую себе - чи живу я зараз, чи щаслива, чи просто виживаю? Наш ворог хоче, щоб ми не жили, не мали повноцінного життя. Про це варто пам'ятати.

Мені здається, що наші жінки дуже вітальні, і мають надзвичайну здатність жити в радості навіть в найстрашніші часи. Ця вітальність також допомагає нам вірити в перемогу і робити кроки до неї.

6. Що/хто вас надихає?

Мене надихає архітектура, зірки в полі влітку, надихають люди, сміливість і талант робити щось нове. Надихають добрі вчинки, емпатія. Склоблоки старих закинутих цегельних заводів, руїни Будянського фарфорового заводу. Надихають «кушурі», дика природа і річка Донець. Звичайно, гарні чоловіки теж.

7. Які (принаймні) три якості ви найбільше любите в собі і чому? Які ваші суперсили?

Люблю мапи і добре орієнтуюсь на місцевості. Вмію гостро з гумором відповісти на агресивні слова співрозмовника. Голосно сміюсь і танцюю вдома.

9. Як ви ставитеся до челенджів? Що спонукає вас рухатися вперед?

Дуже люблю виклики, дедлайни, люблю конструктивну критику, вмію працювати багато і плідно. Оптимізм і добрі слова про мою роботу найбільше надихають.

11. Де інші можуть знайти вас/вашу роботу (посилання на веб-сайти, facebook, блоги тощо)?

instagram: @vika4good

facebook: viktoria.grivina

medium: viktoriagrivina.medium.com

x: brams884

bluesky: brams884

Де ви були, коли стався напад РФ? Чи вірили ви в можливість нападу РФ на ключові міста України і початку повномасштабної агресії?

Була в Сент-Ендрюсі, в Шотландії. Не вірила і перебувала в абсурдній впевненості, що нічого не станеться.

Що Ви відчували в день початку війни? Куди Ви пішли і який, наскільки Ви пам'ятаєте, був Ваш план?

Була в стресовому стані, декілька тижнів мене трясло. Мій план був забрати батьків до Шотландії і самій повернутись до Харкова. Дуже хотіла повернутись, але оцінила власні можливості, і зрозуміла, що в ці перші місяці буду корисніша за кордоном, де можна збирати гроші і лобіювати допомогу.

Як поживають ваші рідні та друзі? Як часто ви з ними спілкуєтеся?

Як колись написав мій тато, «все добре (окрім війни, звісно)». Складно говорити про все добре. Маю знайомих-захисників, що загинули.

Які конкретні дії (великі чи малі) ви зробили і продовжуєте робити, щоб допомогти Україні та українському народу?

В перші місяці робили з іншими студентами багато зборів, вишукували шоломи, бронежилети, тощо, для знайомих, що були в теробороні. Потім сконцентрувалась на культурних подіях. Організувала серію семінарів Spotlight on Ukraine, присвячену енергетиці України підчас війни. Потім ще серію читацьких семінарів з української літератури. Наразі організувала літературну і мистецьку резиденцію в моїй квартирі в Харкові під назвою «Тихий центр». Резиденти приймають участь в онлайн семінарах для іноземної студентської аудиторії, Dispatches from the Quiet Centre.

Чи відчуваєте Ви, що війна змінила Вас? Як саме? Чи здивувало вас щось від початку війни в собі (як ви справлялися з труднощами, залишалися сильними, знаходили натхнення в несподіваних джерелах тощо), у вашій країні, у ваших уявленнях про людяність? Що стало для вас прозрінням?

Звичайно, змінила. Як і Харків, я стала менш наївною, злішою. Моя злість росте із кожним днем, але це позитивна енергія, вона надихає працювати, встигнути більше в цьому житті. Не здивувала, але дуже порадувала людяність і хоробрість харківʼян і всіх українців в перші місяці повномасштабного вторгнення. Це дуже надихало не лежати десь у бездіяльності. Прозрінням стала цинічність, несерйозність західних політичних систем. І дорослість, мудрість, що зʼявилася в багатьох українців.

Чим, на Вашу думку, росіяни відрізняються від українців? Чи хочете ви справедливості для українців? Чи вважаєте Ви, що це можливо і як би Ви хотіли, щоб це сталося?

Мені складно говорити про росіян, я не так багато із ними спілкувалась в житті. Помічала певну зверхність до інших, але не маю достатньої вибірки, щоб стверджувати. Українці часто недооцінюють свої можливості. Ми цінуємо певну хаотичність, що супроводжує всі демократичні процеси. Ми вміємо сміятись, але не грубо, без образ. Російські жарти чомусь завжди містять образу, приниження іншого. Ми уміємо посміятись на собою. Я вважаю, що саме справедливість має бути завершенням цієї війни. Недостатньо повернути території, має бути глибинне розуміння російським народом того страшного злочину, що вони скоїли і усвідомлення причин, що до нього привели.

Що б Ви хотіли, щоб світ знав/усвідомив/зрозумів/поцінував про українців та українок зокрема?

Що Україна - дуже велика країна, найбільша демократія (хоч і не ідеальна демократія) в Європі. Наші простори, різноманіття ландшафтів і локальних культур ще буде відкрито світом.

Як це - жити зараз за межами країни і підтримувати зв'язок зі своєю сім'єю та близькими всередині? Чи можете ви описати це для тих, хто не може відчути це на особистому рівні?

Жити за кордоном мені важче, ніж в Україні. Обстріли сприймаються більш болісно, коли я далеко, страх за рідних підвищується. В Харкові ми всі в одному човні, всі в рівних умовах перед російськими бомбами. За кордоном я - випадково виживша людина серед мільйонів людей, у яких немає війни.

Українці, які живуть за кордоном - неважливо, 1 рік чи 20+ років, чи мають вони якусь відповідальність перед Батьківщиною в цей складний час (діяти, збирати кошти, робити навіть дрібниці)?

Я думаю, бути частиною світової спільноти українців - це усвідомлене рішення, його не можна навʼязувати, це має природньо прийти. Діаспора зберегла безліч українських культурних багатств за радянські часи, зробила все для того, щоб ця культура вижила за будь-яких обставин. Сьогодні будь-хто може вивчити українську, стати частиною нашої культури, стати волонтером чи дослідником нашої історії. І ці люди вже теж українці і частина нашої спільноти.

Що ви зробите в першу чергу, коли Україна переможе? Про що ви мрієте для себе і своєї сім'ї після закінчення війни?

Для моєї сімʼї мрію про гарний будиночок в нас на дачі на Печенігах, і засудити забудовників, що понаставили огорож на березі водосховища.

Після війни поїду на Арабатську стрілку, на Джарилгач, в Крим. Буду сидіти схилі на Демерджі і згадувати 2013, все, що з нами сталося. Допишу книгу про це.