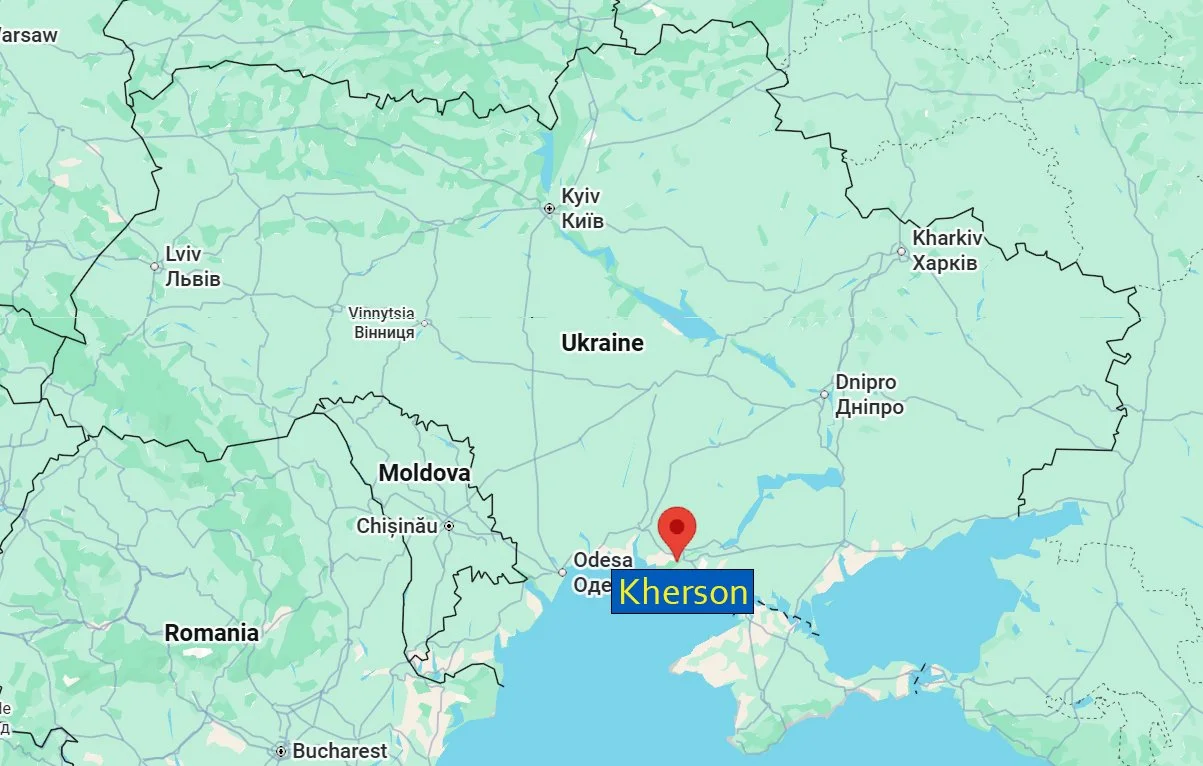

THIS INSIDE UKRAINE STORY IS FROM Kherson

* All images and answers in the feature were provided by the WOW Woman.

INSIDE UKRAINE SERIES: A SNAPSHOT, A DAY-IN-THE-LIFE, A GLIMPSE OF WHAT IT’S LIKE TO LIVE, RESIST, SURVIVE AND PERSEVERE IN A NATION UNDER ATTACK.

GLORY TO THE UKRAINIAN WOW WOMEN, FOR SUPPORTING THEIR COUNTRY AND BRINGING UKRAINE CLOSER TO VICTORY.

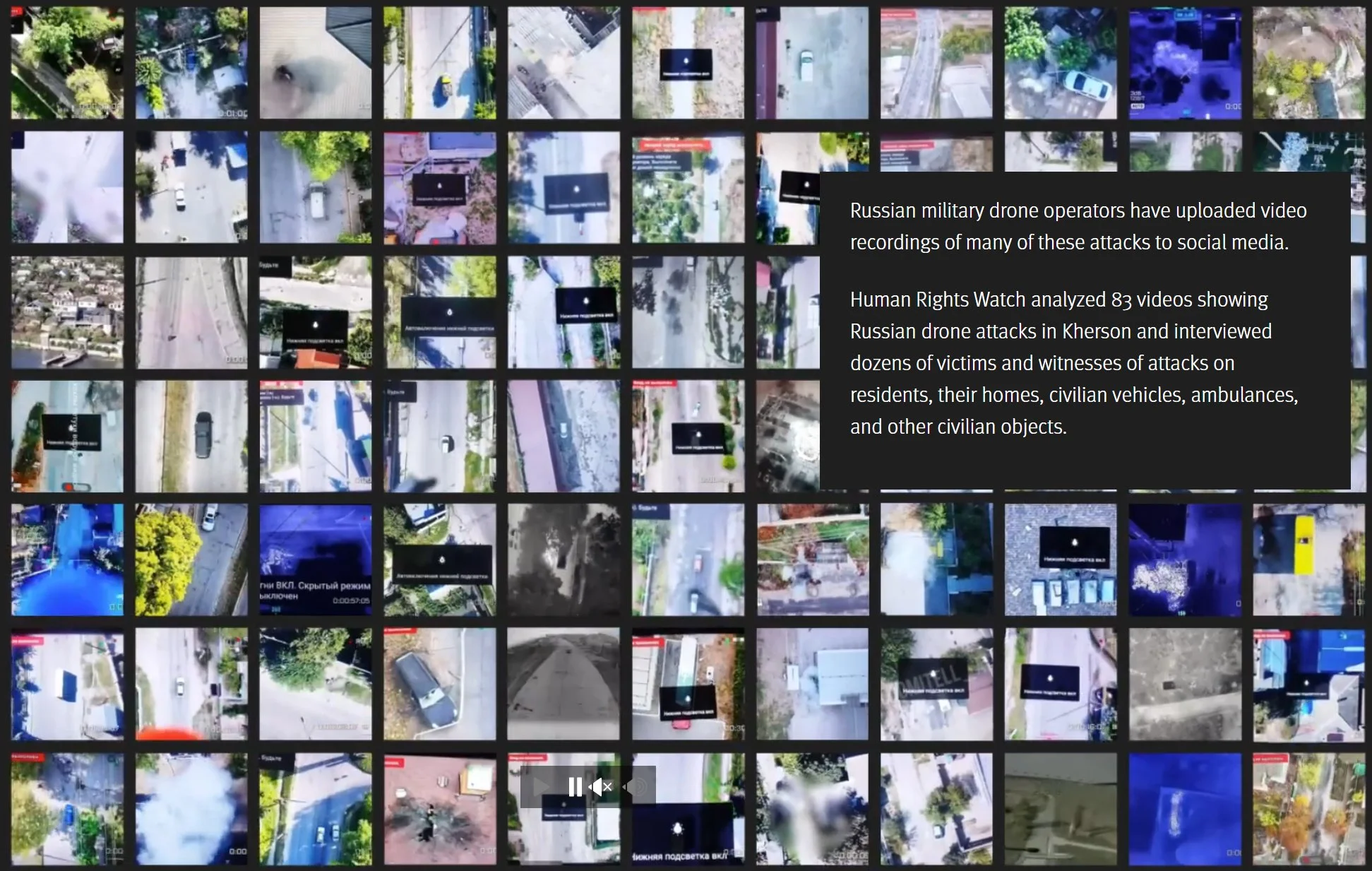

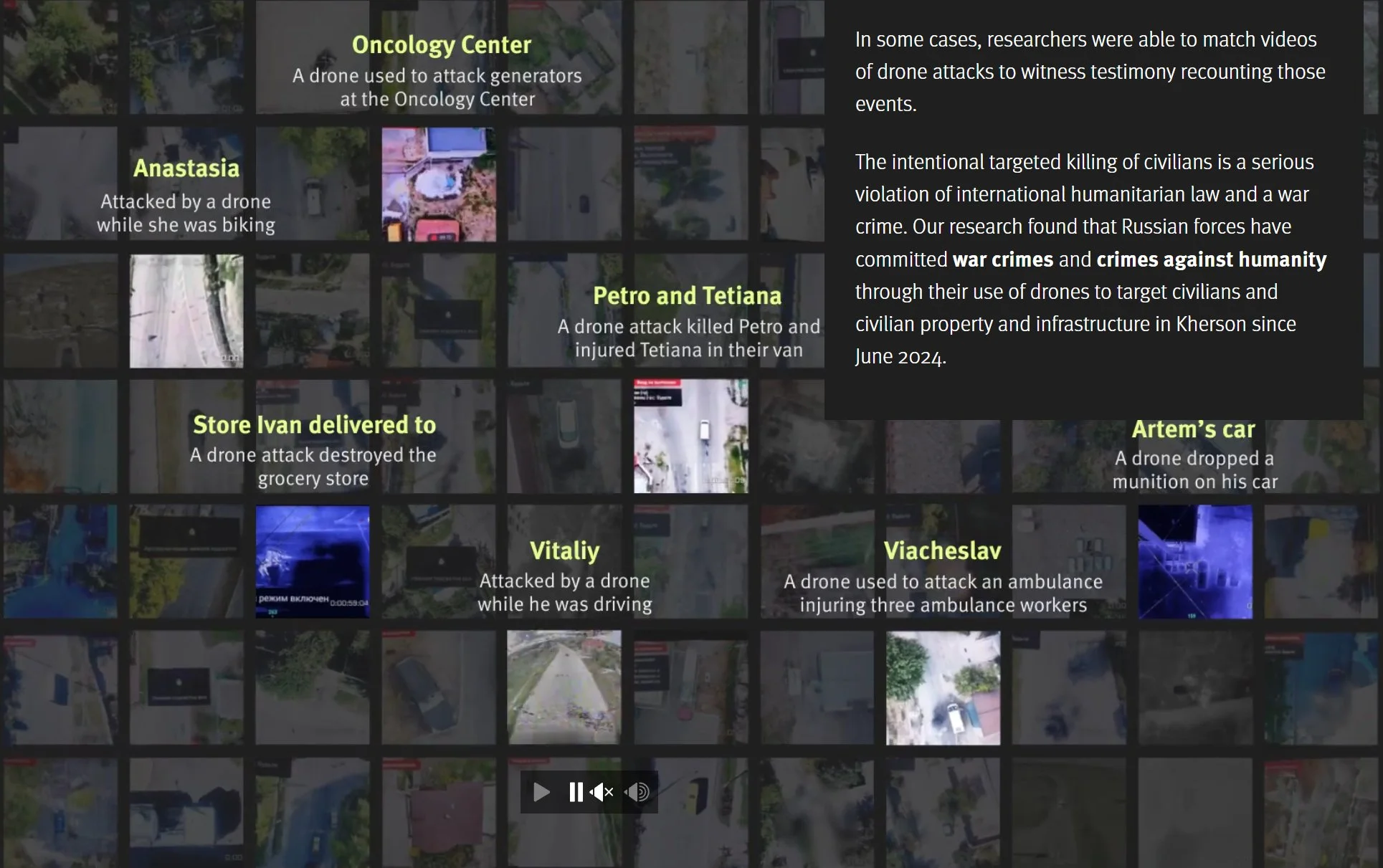

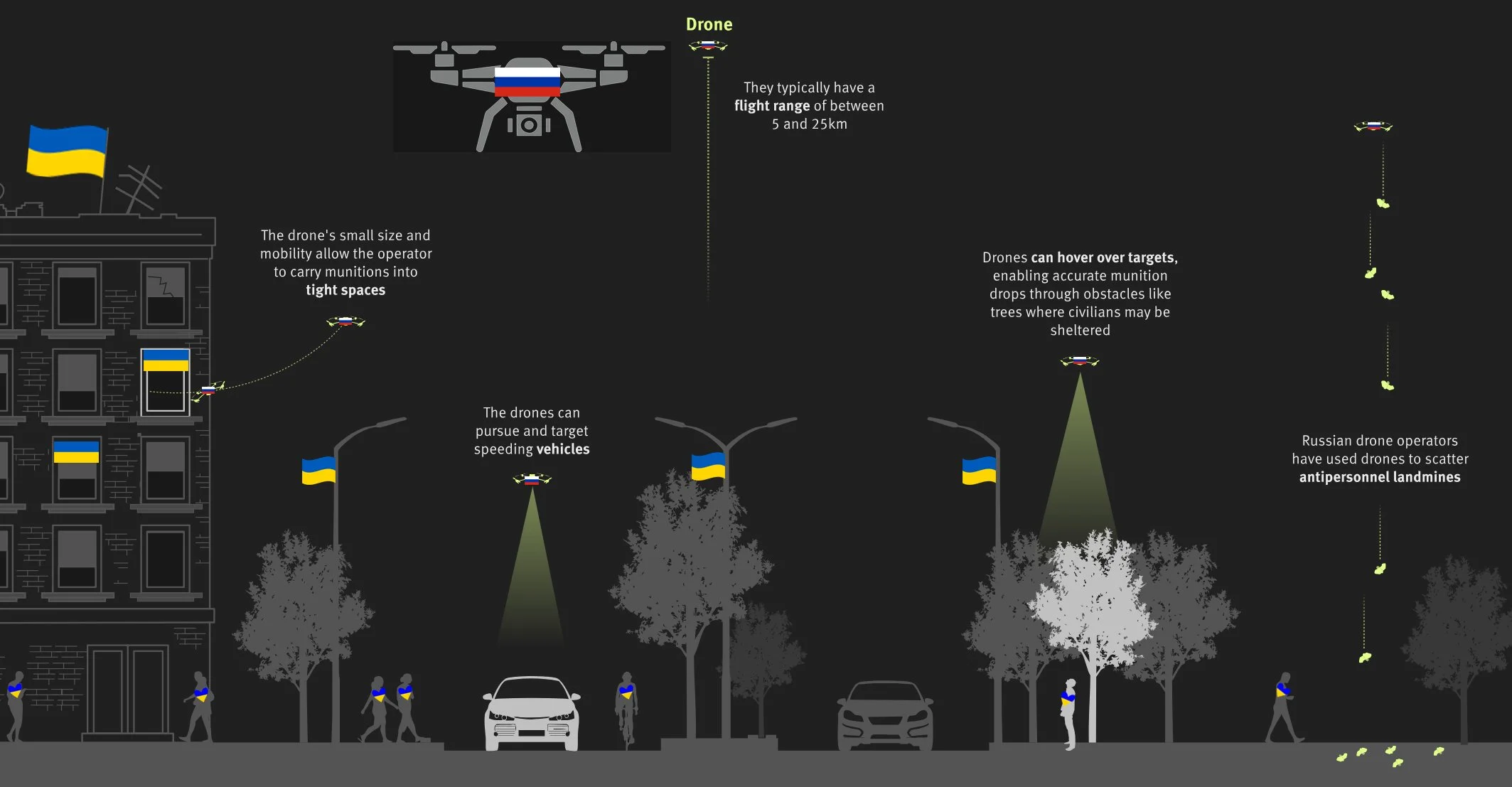

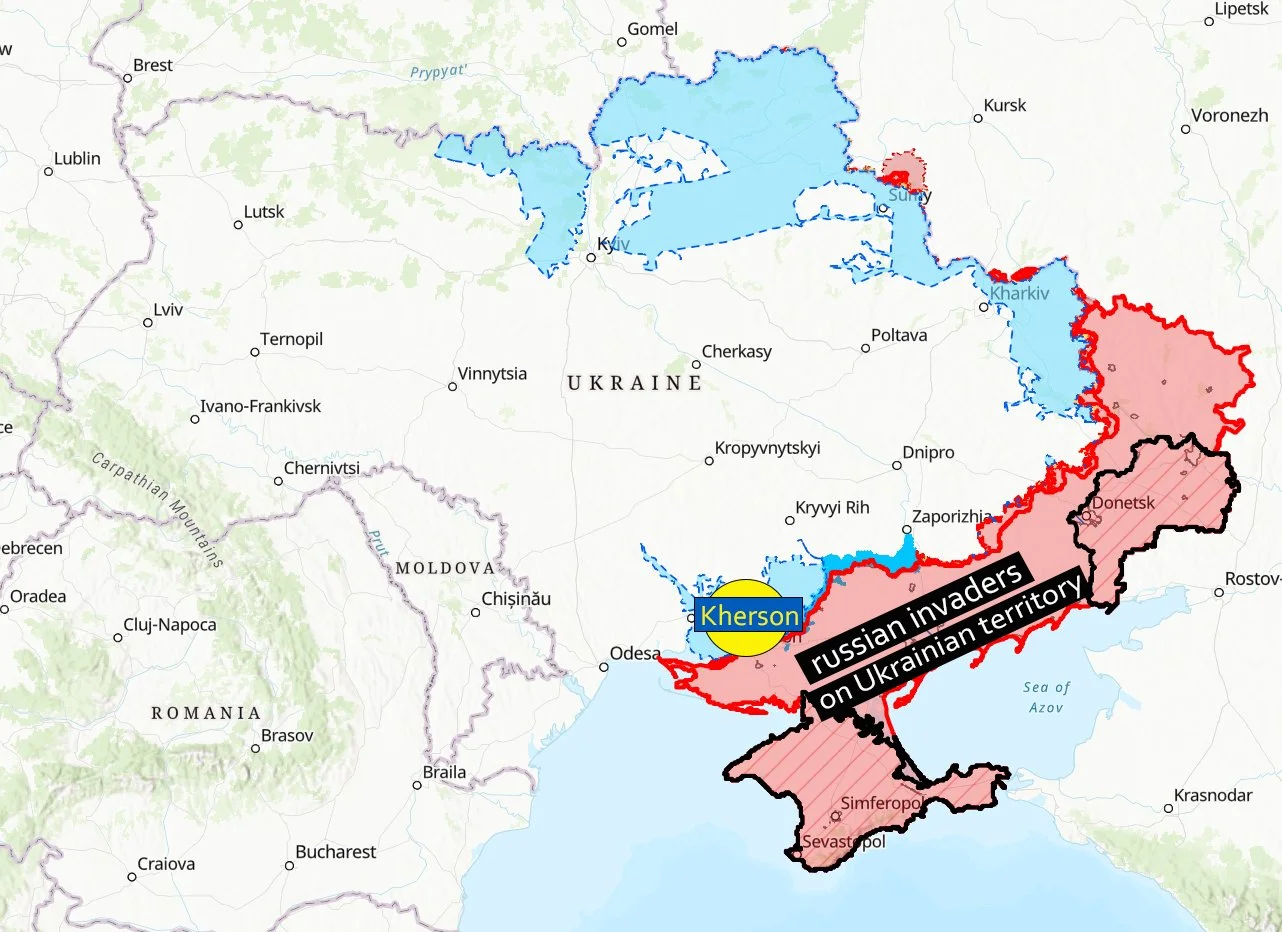

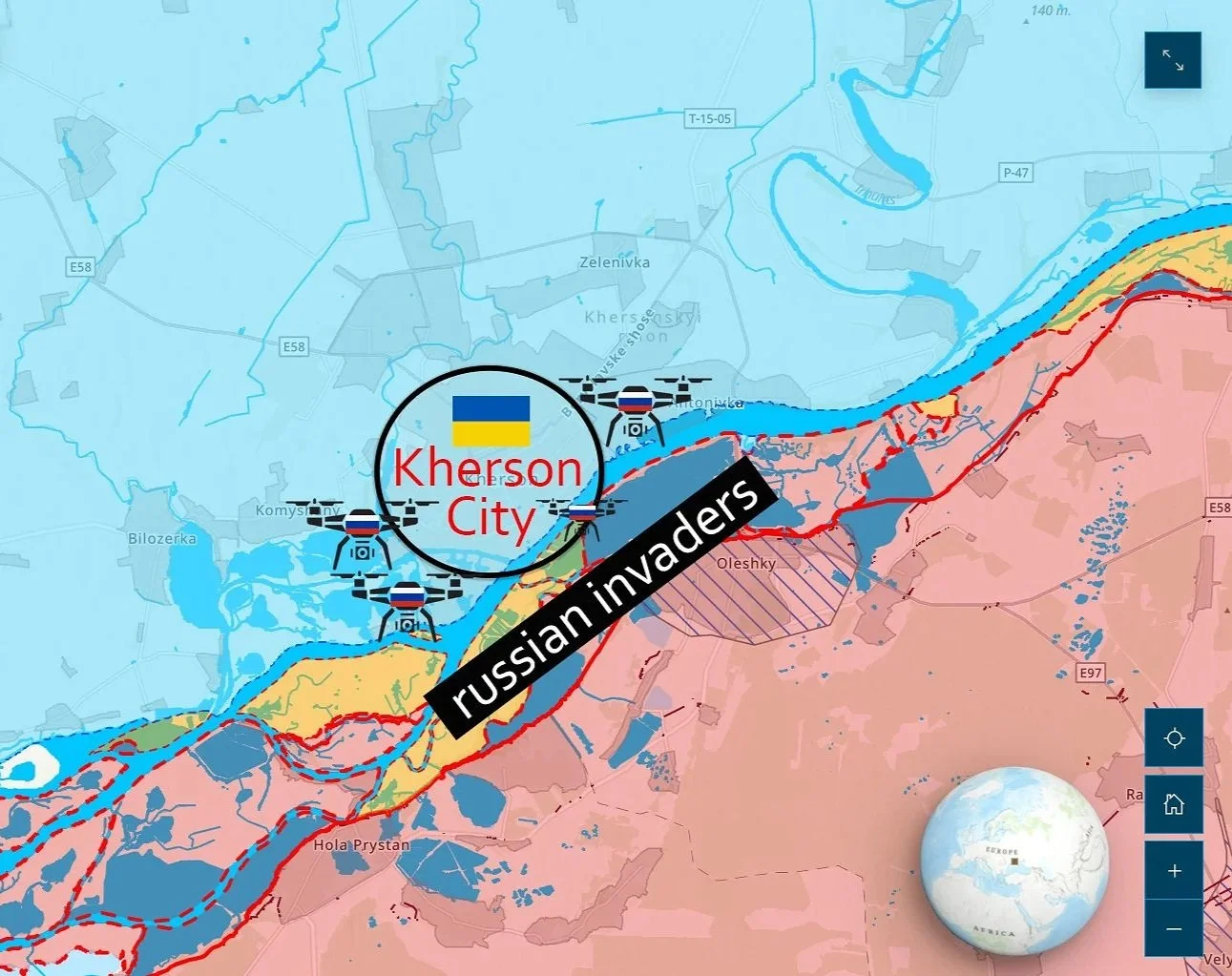

Attention. The southern Ukrainian city of Kherson is under constant russian attack. Ukrainian civilians are deliberately targeted every day. Homes, streets, and entire neighborhoods are bombed repeatedly by russian forces. The violence comes from across the Dnipro River, where the russian aggressor has been pushed back by the Ukrainian army but remains within FPV drone range. From across the river, russian forces launch drones, watch people from the sky, track their movements, and drop explosives on men, women, children, and elderly people. Civilians are hunted while driving to the dentist, walking to church, biking to school, or simply standing outside their homes. This is happening now, as you are reading this text. These are daily crimes against humanity perpetrated by the russian forces who later disseminate the footage of these attacks among the russian social media channels, where it receives tens of thousands of likes and shares.

According to Human Rights Watch, who analyzed countless videos uploaded to russian social media channels, russians use armed drones in large numbers to target, hunt, kill, and injure civilians in Kherson - making life so unbearable that those who are able feel that they must flee. Remaining people have been forced to adapt to the constant threat of armed drones, changing the way they move around their neighborhood, go to work, or secure food, water, and medical care. In some areas, residents have been cut off from the city’s water supply and electricity for months because of incoming russian drone attacks. Often those who remain are the elderly. Such actions by the russian aggressor can be considered a crime against humanity because they knowingly target civilian population and force displacement.

My WOW Woman, Zarina Zabrisky, is speaking loudly and clearly about russia’s atrocities in Kherson. She documents the truth by living among and interviewing people who remain in the city, a population reduced by russian aggressor from 280,000 to roughly 66,000. Zarina bears witness to and lives with the aftermath of relentless and brutal russian bombings. In her documentary, Kherson, Human Safari, Zabrisky focuses on the resilience of the Ukrainian spirit and human dignity. She interviews many impressive Kherson residents who defiantly choose to stay despite russia’s horrors. Kherson is their city, and they refuse to surrender it. Living in Kherson throughout the years of full-scale war, Zarina withstands the same dangers, including attacks on her residential building. Zarina reports on what it’s like to exist and persevere under constant russian drone surveillance.

Zarina’s voice and her documentary matter because after almost four years of full-scale war, russia’s violence in Kherson has not stopped. Drone attacks and shelling repeat daily. Ukrainian civilians continue to be hunted and killed. While international attention moves on, Kherson does not get a pause. Zarina Zabrisky is working to make sure the world understands what is happening in Kherson right now. She walks the talk by remaining in the city, standing with its people, and refusing to look away. She is a brave WOW Woman, and I am proud to share her work.

- Olga Shmaidenko, Founder of WOW Woman. Inside Ukraine is a WOW Woman series documenting the voices of Ukrainian women during the full-scale russian invasion. It bears witness to the human cost of war and to Ukrainian women’s refusal to be silenced.

Fearless Journalist, Author, Filmmaker, Kherson, Ukraine

1. Name.

Zarina Zabrisky.

2. What did you study and what is your profession?

I studied literature and languages. I am an author, journalist, and filmmaker.

3. Where were you when the full scale russian attack took place? Did you believe in the possibility of the RF attacking key cities of Ukraine and starting a full-scale aggression?

I was in San Francisco, finishing my second novel.

The war had been going on since 2014, and there were 100,000 Russian soldiers at the Ukrainian border. One just had to open their eyes and see what was happening, but the world chose denial. I have been warning about it for a long time.

What was your experience of the day the war started?

I was working for a bookstore channel at the time. I quit that job and started to report on the developments in Ukraine the moment Putin made his “speech.” It was the longest Twitter thread, maybe a Guinness World Record, as I only stopped when I relocated to Ukraine to report from the ground. I translated Ukrainian and sometimes Russian Telegram channels and posted several times an hour with updates on all fronts, around the clock. I think I was manic as I have not left my house for weeks, and hardly slept. I anticipated the full-scale invasion but it didn’t make it easier.

Where did you go and what do you recall was your plan?

I first wanted to join the International Legion and fight, but realized that I would be more useful as a reporter. I applied for accreditation with the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense as a journalist for Byline Times, the newspaper I wrote for, and waited to get it. As soon as I got it, at the end of March 2022, I went to Odesa and started reporting. After a couple of months, I started my travels all around Ukraine and began reporting from the front.

I am now based in Kherson, Ukraine.

4. What was your typical day like before the war and how has your role changed since the invasion of Ukraine?

Before the war, I was finishing my novel. Most days, I was writing, with short breaks for walks and working out. I have dropped it, and now it is reporting all day, with field trips and interviews, and writing and editing the rest of the time, with breaks for working out.

5. Where were you born and where do you live now?

I don’t believe a person is defined by the place of birth but by the place they choose to live. I didn’t choose to be born in the USSR, but I chose to live most of my life in the USA and the last three years in Ukraine.

6. What would you say are your strengths and superpowers?

I don’t have any superpowers. I am enraged by Russians and love Ukraine, so this keeps me going. I am also very obstinate and persistent. And my ancestors were from Ukraine - maybe that is my superpower. I guess, I can say that I am a solid writer, which helps.

7. What are some concrete actions (big or small) you’ve done and continue doing to help Ukraine and Ukrainian people?

Never enough but I am proud that I helped fight the invaders and was put on the list of personal sanctions “stop list” by the Russian Federation, including a ban on entry into the Russian Federation.

In July 2024, I uncovered and reported on a disturbing new form of warfare and war crimes unfolding in Ukraine, which I have termed the “human safari.” This tactic involves the systematic deployment of small, remote-controlled drones - specifically First Person View (FPV) drones, to deliberately hunt and target civilians in frontline regions, including Kherson, Sumy, Kharkiv, and Nikopol. These drones carry out precision attacks on civilian targets by dropping anti-personnel mines, incendiary substances, explosives, and sharp objects on human beings, residential buildings, vehicles, hospitals, and emergency responders. Such attacks are often filmed and disseminated through Russian Telegram channels, thereby weaponizing terror as part of a broader psychological warfare strategy.

Based on reports from the United Nations and Human Rights Watch in 2025 (to which I have contributed contact lists and other materials), these actions have been classified as war crimes and crimes against humanity. It means that the military command, including Putin, can be brought to trial. I have presented these findings at the German Bundestag and U.S. Congressional offices in 2025.

I directed a full-length documentary Kherson: Human Safari, which is endorsed by the Armed Forces of Ukraine, Ukrainian Navy, Kherson Military Administration, and the official media of the Office of the President of Ukraine. The film has received coverage by many publications around the world and is scheduled for screening on Capitol Hill in September 2025. It is now being screened around the world, including Paris, Dallas, New York, Bonn, Melbourne, Riga, and more, translated into many languages, and it helps raise awareness and, I hope, save Kherson.

I have been writing about hybrid warfare, Russian intelligence operations, and information warfare since 2015, and have taught seminars on Kremlin combat propaganda to international audiences. As a journalist embedded in southern Ukraine since the start of the full-scale invasion in 2022, I’ve covered how Ukrainian forces - including the military, SBU, Special Forces, and local partisans. have used asymmetric tactics to resist and repel a larger occupying force. From sabotage operations and drone warfare to psychological campaigns and civilian resistance networks, I’ve reported firsthand on how innovation, intelligence sharing, and decentralization have reshaped the battlefield. I’ve interviewed Ukrainian Special Forces, civilians cooperating with intelligence services, and cyber defense volunteers, and would bring sharp, grounded insight to moderating or contributing to this panel, showing how Ukraine is redefining 21st-century warfare for smaller nations under existential threat.

Byline Times, an exclusive interview with Ukrainian Special Forces officers, “An Urgent Warning to the West From the Ukrainian ‘Elves’ Fighting Russian Infiltration”

Byline Times, Unmasking the Coordinated Reach of Russian Doppelgänger Bots. My investigation into the Doppelgänger disinformation campaign was included in 24 internal Kremlin documents delivered to the Russian Presidential Administration, and later was cited in an FBI affidavit supporting the seizure of Russian-linked domains, demonstrating the impact of my reporting on countering information warfare.

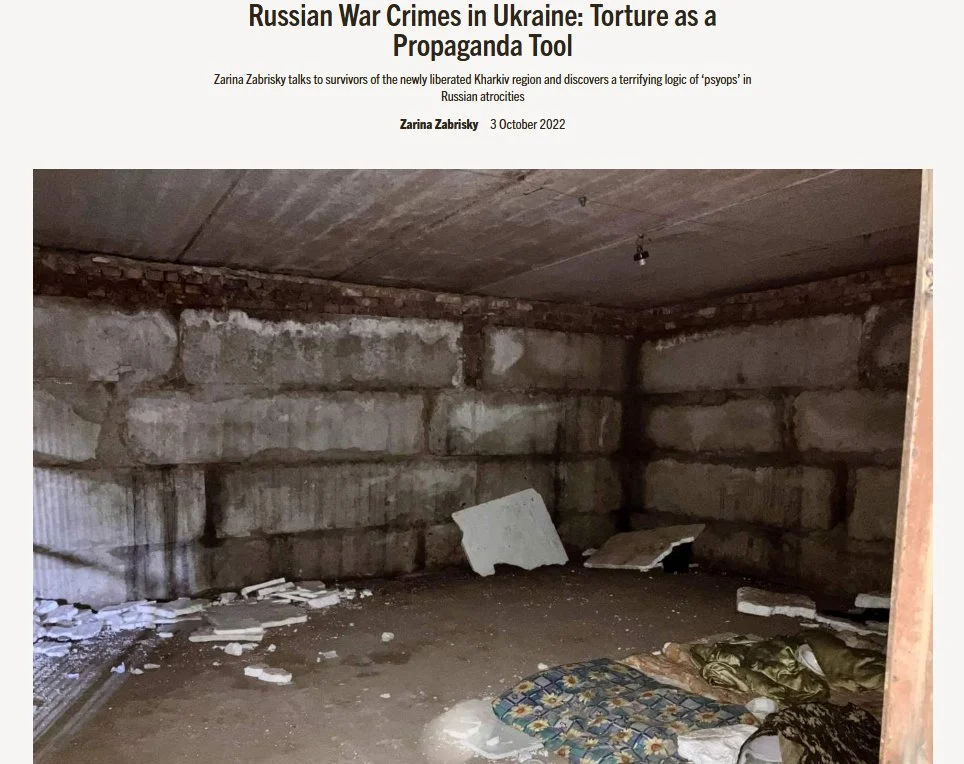

I have covered Russia’s system of abduction, filtration, and torture since 2022, and interviewed former POWs, hostages, and investigators. My fieldwork includes documenting war crimes and psychological trauma among survivors, especially in occupied and later liberated areas such as Kherson, Kharkiv, and Zaporizhzhia. I interviewed both returning Ukrainian POWs and Russian POWs in Ukrainian prisons. Based on some of my research, I co-produced an award-winning documentary, Under Deadly Skies.

Byline Times, Russian War Crimes in Ukraine: Torture as a Propaganda Tool

Voice of America, Interviews with former and survivors of Russian torture

8. Can you talk about Kherson, the city that was prior to the full-scale and the city now?

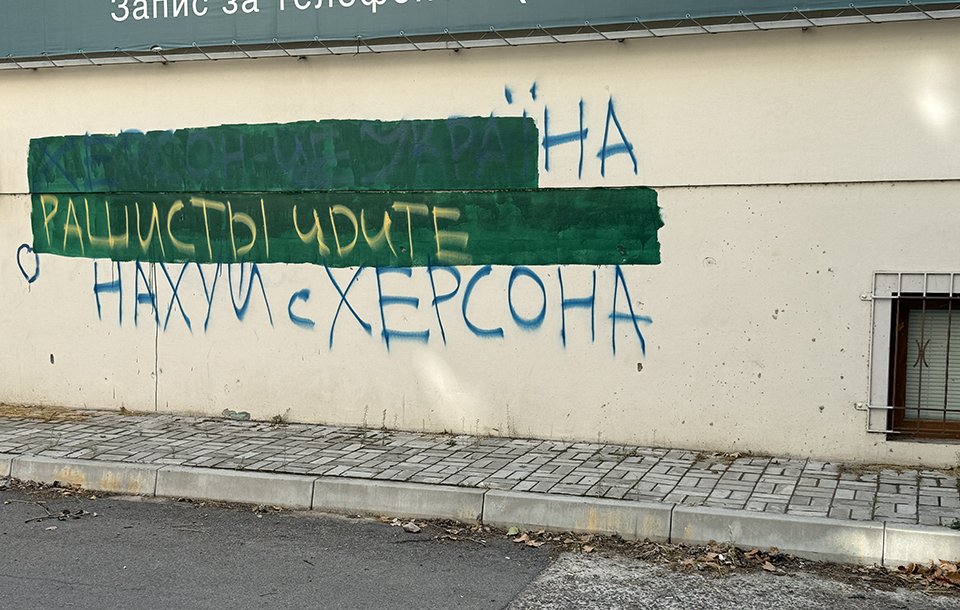

I have never visited Kherson before it was liberated. I published some interviews with people who fled Kherson then, but I have never experienced peaceful Kherson. When I first came, it was pretty intact, with just a few buildings destroyed here and there. During the two years of my life here, I have seen downtown Kherson crumbling and becoming empty like Pripyat or a ghost town on Route 66 in America. I see more and more buildings destroyed daily, despite Khersonians trying to clean the streets after every explosion, plant flowers, and even decorate. Each time Russians hit, Ukrainians restore but it is an uneven fight at this moment. Reconstruction under artillery fire, aerial bombs, and drones is impossible. The façade of the White House, ruined by the Russians became a symbol of their barbarism. It is just sitting there, in the Freedom Square, as an eyewitness to the crimes.

What are some aspects of the city and the people that leave you inspired to keep returning there and bring more stories to light about the atrocities that russians are carrying out there?

The love of life. Blooming rose gardens in front of the ruins. Watermelons and pumpkins by the carcasses of the buildings. Tomatoes and sunflowers growing on top of the temporary bomb shelters. Water trays and bread crumbs set up for pigeons in the streets. Recycling under fire. Old and young people exercising in the parks to the sounds of explosions. Boxing, dance and yoga studios thriving, even if not everyone can make it to the class due to the drone hovering above. Theater premieres, poetry readings, music concerts, and art exhibits in the basements. Libraries and book clubs open and throwing master classes during aerial bomb attacks. Alleys and boulevards lined up by shrapnel-scratched sycamores, streets covered by orange leaves in the fall, even if anti-infantry mines are hiding underneath the leaves. Sunlight playing on crumbling walls and balconies. The river glistening so close and so impossible to reach. The sounds of cicadas in summer, at night, interrupted by Shahid drones. My little corner store bodega, where the sales lady is more savvy about politics than most analysts I interview. The big fancy grocery store with dragon fruits, smoked tofu, kombucha, its own bakery with the best in the world hot black bread, the walls decorated with the paintings by the local primitivist artist. Everything, really.

9. What are things you do just for you?

Yoga, going to the bath (banya) with my girlfriends, going for a walk, sometimes dancing. Not much time to do everything I want.

Is it possible to stay sane in a war situation?

I don’t think so.

What are some things that help you to not lose yourself?

Who said I didn’t? Lifting weights, yoga. Makeup, it is a bit of a meditation that calms my nerves, a ritual when you are focused on yourself.

A Human Being behind the news stories

“A russian drone killed 84-year-old woman Larisa Myronivna Vakulyuk, known as Grandma Lora in Kherson as she was walking her goats”, The New York Post reports.

In a September interview with Zarina Zabrisky, Lora said: “Everyone is afraid, but everyone still has hope.”

Grandma Lora, died instantly when a Russian FPV drone struck her and her two goats in the Antonivskyi district of Kherson. She was clearly hunted down by a russian FPV drone pilot.

Journalist Zarina Zabrisky, who had interviewed Vakulyuk a month earlier, described the aftermath: “Her legs were torn off, she was ripped to pieces. In my three and a half years covering this war, I have seen many deaths, but this was one of the hardest to witness.”

Grandma Lora’s remains were discovered alongside her dead goats, confirming that she died instantly and that the strike occurred during her morning walk. The deadly attack was one of several that struck the area, as four other individuals were hurt while multiple buildings and vehicles suffered significant damage from the drone strikes.

10. Do you feel the war changed you? How?

Yes. I like to spend more time by myself. I never liked loud sounds but now I am really sensitive to them. It is hard to tell otherwise…

Since the start of the war, has anything surprised you about yourself (how you have handled yourself, remained strong, found inspiration in unlikely sources, etc.)? I am not that focused on myself, so it is hard to tell. It feels right to be doing what I am doing, I guess, so it might be surprising—this is not what I have planned.

about your country? Yes, my country of birth (russia) went insane and became fascist, and it really broke my heart. I really believed in America and loved it. Still do, but it is becoming much harder. I am not even sure if I have a country. Ukraine is the land of my ancestors and is becoming my home. Still, I cannot call it my country, yet.

about your ideas about humanity? I had no illusions about humanity before but the war truly makes it black-and-white and harsh. I have seen horrendous things, and I have also seen a lot of noble and amazing things.

What have been some of your epiphanies?

I guess I am not in a place where I can make conclusions or have the mental capacity for summing it up. I am in the midst of “action” with Russian drones dropping explosives by my window a few times a day. Just a few hours ago, four aerial guided bombs were dropped on a Kherson suburb. Until they dropped, we didn’t know where they’d hit, could have been anywhere. So you are just walking down the street, wondering if you are being watched from above and if you will die today. Or you go to bed and you don’t know if you will wake up because of all the explosions outside. Every night. I guess this is the epiphany: any safety is an illusion, and life is monstrously fragile and can end at any moment, so I have to live it fully as much as possible in the moment. Not leaving it for tomorrow. Tomorrow should not be taken for granted. In fact, tomorrow is a gift (not to sound like a fortune cookie).

11. What do you want the world to know about Ukrainians at this moment in time? About Ukrainian women?

Ukrainians are not victims. Ukraine values agency and will above all. It deeply resonated with me: just as I refuse to be defined of being born in the USSR, Ukraine fights for its identity outside of the mental framework of the post-Soviet space.

Ukrainian women are powerful and beautiful. I am at a loss for words for their strength of spirit and bodies. They are also very athletic and grounded in their bodies. I also appreciate the dignity and elegance, and attention to detail in appearance. In Kherson, no one walks around disheveled, no matter what. Beauty against barbarism.

12. Who are your WOW Women who inspire you?

I am reading a book about American women correspondents in World War I now, and I find inspiration in their experiences and writing. Nellie Bly, for instance. The same goes for women war journalists in WWII, like Lee Miller, one of my major inspirations.

My girlfriends from the yoga and dance studio in Kherson inspire me every day. They are soulful, strong, kind, and always fun. They have lived and are still living through hell. The dancer in my film, for instance, Alyona - so multi-dimensional, talented, hard-working, and also modest.

13. In your opinion, how do russians differ from Ukrainians?

Different history, different national character. Russians lived under serfdom of various kind forever. Freedom and free will are empty sounds to them.

Ukrainians not just believe in agency, they impersonate it and live it. Ukraine is defined by free choice. The “No Fate” slogan at the last Burning Man is a good illustration of this. Ukrainians are also very hard-working, unlike Russians, who tend to appropriate.

And Ukrainians are insanely clean. I mean, streets, houses, and trenches, even. A different standard of living.

Of course, these are generalizations, and I am aware of lazy and fatalistic Ukrainians, and I have met in my life a few Russians who died for freedom.

Like I said, one is not defined by the birth circumstances. There is a freedom of choice.

Do you want justice for russians? Do you think it is possible, and what would you like to see happen?

Yes. I believe in collective responsibility. I want tribunals and trials. I hope my reports will be used as evidence. I believe that anything is possible. We just need to work hard and make it happen.

14. How do you see dynamics changing inside the country, with attitudes toward those who left vs those who stayed? Do you think that Ukrainians who left the country have a specific responsibility toward their homeland?

I do see all kinds of attitudes; it really depends on a person. And on the region.

In Kherson, I do feel that people are becoming more and more exhausted with the horrors befalling them, and, as a result, they lose tolerance or patience towards those who have left and are not helping out.

I can’t talk for other people, though. I can tell you that I was very upset with the attitude of some Ukrainians in the US and Europe during my last visits, ranging from indifference to open hostility and refusal to help Ukraine. It is not my place to judge, though. I am here to report.

15. What is a place or activity that makes you feel happiest?

Right now? Yoga studio here, and walking down the streets of old Kherson.

16. What will be the first thing you’ll do when Ukraine wins?

I will drink the Bakhmut-made champagne with my closest friends in Odesa. We have been waiting for a while. I will also go dancing, both in Odesa and Kherson.

What are your dreams for yourself and your family after the war is finished?

I want to go to Australia and explore the folklore of the Aboriginal people. I also want to go to Madagascar and see all the animals there. I want to hang out on the Langeron beach in Odesa, eat cherries, drink cocktails, and read novels. I want to walk to the Dnipro River in Kherson and touch the water; I have never been able to do it in my three years here. I want to see the left bank with all its beauty. I want to go to the Ukrainian Crimea! God, there is so much I want to do!

17. Where can others find you/your work? (links to website, blog, etc.)

You can watch my documentary at www.khersonhumansafari.com

I am a war correspondent for Byline Times, Euromaidan Press, Fresno Alliance, and I write and report for other publications, including BBC Radio. I post links to my work and reports daily on my social media: X @ZarinaZabrisky; Instagram @zarinazabrisky, Facebook @zarina.zabrisky, BlueSky, YouTube. A lot of my pre-full-scale invasion articles can be found at Medium.

ЦЯ ІСТОРІЯ "INSIDE UKRAINE", З Херсона.

* Всі зображення та відповіді у матеріалі були надані WOW Woman

СЕРІЯ INSIDE UKRAINE/ВСЕРЕДИНІ УКРАЇНИ: МОМЕНТАЛЬНИЙ ЗНІМОК, ОДИН ДЕНЬ З ЖИТТЯ, ПОГЛЯД НА ТЕ, ЯК ЦЕ - ЖИТИ, ЧИНИТИ ОПІР, ВИЖИВАТИ І НЕ ЗДАВАТИСЯ В КРАЇНІ, ЯКА ПЕРЕБУВАЄ ПІД ЗАГРОЗОЮ.

СЛАВА УКРАЇНСЬКИМ ВАУ-ЖІНКАМ, ЯКІ ПІДТРИМУЮТЬ СВОЮ КРАЇНУ І НАБЛИЖАЮТЬ УКРАЇНУ ДО ПЕРЕМОГИ.

Увага. Південне українське місто Херсон перебуває під постійним російським обстрілом. Українські цивільні громадяни щодня стають об'єктом цілеспрямованих атак. Російські війська неодноразово бомбардують будинки, вулиці та цілі райони. Насильство походить з іншого берега Дніпра, де російський агресор був отіснений українською армією, але залишається в зоні досяжності безпілотників FPV. З іншого берега річки російські війська запускають безпілотники, спостерігають за людьми з повітря, відстежують їхні пересування та скидають вибухівку на чоловіків, жінок, дітей та людей похилого віку. Цивільних громадян переслідують, коли вони їдуть до стоматолога, йдуть до церкви, їдуть на велосипеді до школи або просто стоять біля своїх будинків. Це відбувається зараз, коли ви читаєте цей текст. Це щоденні злочини проти людства, скоєні російськими військами, які згодом поширюють відеозаписи цих атак у російських соціальних мережах, де вони отримують десятки тисяч лайків і репостів.

За даними Human Rights Watch, яка проаналізувала безліч відео, завантажених на російські соціальні мережі, росіяни масово використовують озброєні дрони для націлювання, полювання, вбивства та поранення цивільних осіб у Херсоні, роблячи життя настільки нестерпним, що ті, хто має таку можливість, відчувають необхідність тікати. Ті, хто залишився, змушені пристосовуватися до постійної загрози з боку озброєних дронів, змінюючи спосіб пересування по району, добирання до роботи або забезпечення їжею, водою та медичною допомогою. У деяких районах мешканці вже кілька місяців позбавлені водопостачання та електроенергії через атаки російських дронів. Часто ті, хто залишається, це люди похилого віку. Такі дії російського агресора можна вважати злочином проти людяності, оскільки вони свідомо націлені на цивільне населення і примушують його до переселення.

Моя WOW-жінка, Заріна Забріскі, голосно і чітко говорить про звірства росіян у Херсоні. Вона документує правду, живучи серед людей, які залишилися в місті, чисельність населення якого російський агресор скоротив з 280 000 до приблизно 66 000, і беручи у них інтерв'ю. Заріна є свідком і живе з наслідками безжальних і жорстоких російських бомбардувань. У своєму документальному фільмі «Херсон, людське сафарі» Забріскі зосереджується на стійкості українського духу та людській гідності. Вона бере інтерв'ю у багатьох вражаючих мешканців Херсона, які, незважаючи на жахи росії, вирішили залишитися. Херсон, це їхнє місто, і вони відмовляються його здавати. Живучи в Херсоні протягом років повномасштабної війни, Заріна стикається з тими ж небезпеками, включаючи атаки на її житловий будинок. Заріна розповідає, як це - існувати і витримувати постійне спостереження російських дронів.

Голос Заріни та її документальний фільм мають значення, тому що після майже чотирьох років повномасштабної війни насильство росії в Херсоні не припинилося. Атаки дронів і обстріли повторюються щодня.

Українських цивільних громадян продовжують переслідувати і вбивати. Поки міжнародна увага переходить на інші події, Херсон не отримує перепочинку. Заріна Забріскі працює над тим, щоб світ зрозумів, що зараз відбувається в Херсоні. Вона дотримується своїх слів, залишаючись у місті, стоячи разом з його мешканцями і відмовляючись відвертати погляд. Вона - смілива WOW-жінка, і я пишаюся тим, що можу поділитися її роботою.

- Ольга Шмаіденко, засновниця WOW Woman.

БЕЗСТРАШНА ЖУРНАЛІСТКА, ПИСЬМЕННИЦЯ, РЕЖИСЕРКА

1. Ім’я.

Заріна Забріскі.

2. Що ви вивчали і яка ваша професія?

Я вивчала літературу та мови. Я – письменниця, журналістка та режисерка.

3. Де ви були, коли почалося повномасштабне російське вторгнення?

Я була в Сан-Франциско, закінчувала свій другий роман.

Чи вірили ви в можливість того, що РФ атакує ключові міста України і розпочне повномасштабне вторгнення?

Війна триває ще з 2014 року, а на українському кордоні стояли 100 000 російських солдатів. Треба було лише відкрити очі і побачити, що відбувається, але світ вирішив це заперечувати. Я давно про це попереджала.

Яким було ваше враження від дня, коли почалася війна?

На той час я працювала в книжковому магазині. Я звільнилася з роботи і почала висвітлювати події в Україні з того моменту, як Путін виголосив свою «промову».

Це була найдовша серія дописів у Твіттер, можливо рекорд Гіннеса, бо я зупинилася лише тоді, коли переїхала до України, щоб вести репортажі з місця подій. Я перекладала українські, а іноді й російські телеграм-канали і цілодобово декілька разів на годину публікувала оновлення з усіх фронтів. Думаю, я була у маніакальному стані: не виходила з дому тижнями і майже не спала. Я передбачала повномасштабне вторгнення, але це не полегшувало ситуацію.

Куди ви поїхали і який був ваш план?

Спочатку я хотіла вступити до Міжнародного легіону та воювати, але потім зрозуміла, що буду кориснішою як репортер. Я подала заявку на акредитацію в Міністерство оборони України як кореспондент Byline Times (я писала для цієї газети) і чекала, поки її схвалять. Тож щойно я отримала підтвердження, наприкінці березня 2022 року, я поїхала до Одеси і почала писати репортажі. Через декілька місяців я вирішила подорожувати Україною і писати репортажі з фронту.

4. Яким був ваш звичайний день до війни і як змінилася ваша роль після вторгнення РФ до України?

До війни я закінчувала свій роман. Більшість днів я писала, роблячи короткі перерви на прогулянки та тренування. Я припинила це. І тепер цілими днями роблю репортажі з місця подій та беру інтерв’ю, а решту часу пишу та редагую, роблячи перерви на тренування.

5. Де ви народилися і де живете зараз?

Я вірю, що людину визначає не місце народження, а місце, яке вона обирає для життя. Я не обирала народитися в СРСР, але я обрала більшу частину свого життя прожити у США й останні три роки – в Україні.

6. Які, на вашу думку, ваші сильні сторони та надздібності?

Я не маю суперсили. Мене розлютили росіяни, і я люблю Україну, тому це дає мені сили рухатися вперед. Я також дуже вперта і наполеглива. А ще мої предки були з України – можливо, це і є моя надздібність. Гадаю, можу сказати, що я добра письменниця, яка допомагає.

7. Які конкретні дії (великі чи малі) ви зробили і продовжуєте робити для того, щоб допомогти Україні та українцям?

Цього ніколи не буде достатньо, але я пишаюся тим, що допомогла боротися із загарбниками і була внесена до «стоп-листа» Російської Федерації – списку осіб, яким заборонено туди в’їзд.

У липні 2024 року я із занепокоєнням виявила нову форму ведення війни та воєнні злочини, що відбуваються в Україні, – те, що назвала «людським сафарі», і повідомила про це. Ця тактика передбачає систематичне використання невеликих дистанційно керованих дронів, зокрема дронів з видом від першої особи (FPV), для цілеспрямованого полювання на цивільних осіб у прифронтових регіонах – Херсоні, Сумах, Харкові та Нікополі. Ці дрони здійснюють точні атаки на цивільні цілі, скидаючи протипіхотні міни, запальні речовини, вибухові речовини та гострі предмети на людей, житлові будинки, транспортні засоби, рятувальників. Такі атаки часто знімають на відео та поширюють через російські телеграм-канали, тим самим використовуючи терор як зброю у межах психологічної війни.

На підставі звітів Організації Об’єднаних Націй і Human Rights Watch за 2025 рік (до яких я додала списки контактів та інші матеріали), ці дії були класифіковані як воєнні злочини та злочини проти людяності. Це означає, що військове командування, включаючи Путіна, може бути притягнуте до суду. Я представила ці висновки у німецькому Бундестазі та в офісі Конгресу США у 2025 році.

Я зняла повнометражний документальний фільм «Херсон: Людське сафарі», який підтримали Збройні сили України, Військово-морські сили України, Херсонська військова адміністрація та офіційні медіа Офісу Президента України. Інформацію про фільм було висвітлено в багатьох світових виданнях і планується його показ на Капітолійських пагорбах у вересні 2025 року. Зараз фільм показують у всьому світі, зокрема в Парижі, Далласі, Нью-Йорку, Бонні, Мельбурні, Ризі та інших містах, перекладено багатьма мовами. Це допоможе підвищити обізнаність і, сподіваюся, врятувати Херсон.

З 2015 року я пишу про гібридну війну, операції російської розвідки та інформаційну війну, а також проводжу семінари для міжнародної аудиторії на тему воєнної пропаганди Кремля. Як журналіст, який перебуває на півдні України з початку повномасштабного вторгнення в 2022 році, я висвітлювала, як українські сили, зокрема армія, СБУ, спецпідрозділи та місцеві партизани, використовували асиметричні тактики для опору та відбиття численніших окупаційних сил. Від диверсійних операцій і війни з використанням дронів до психологічних кампаній і мереж цивільного опору – я з перших вуст повідомляла про те, як інновації, обмін розвідданими та децентралізація змінили форми поля бою. Я брала інтерв’ю в українських спецпризначенців, цивільних осіб, які співпрацюють із розвідслужбами, та волонтерів кіберзахисту, і можу поділитися своїм чітким обґрунтованим баченням як модератор або учасник панелі, показуючи, в який спосіб Україна переосмислює війну XXI століття для менших держав, що перебувають під екзистенційною загрозою.

Byline Times. Розкриття скоординованої діяльності російських ботів-двійників.

Моє розслідування кампанії дезінформації «Двійник» було занесено до 24 внутрішніх документів Кремля, переданих до адміністрації президента РФ. Згодом це розслідування було процитоване в афідавіті ФБР, що супроводжував арешт доменів, пов’язаних із Росією. Це демонструє вплив моєї журналістської роботи на протидію інформаційній війні.

Я висвітлюю російську систему викрадень, фільтрації та тортур із 2022 року, а також брала інтерв’ю у звільнених військовополонених, заручників і слідчих. Моя польова робота передбачає документування воєнних злочинів і психологічних травм серед постраждалих, особливо в окупованих і пізніше звільнених регіонах, як-от: Херсон, Харків і Запоріжжя. Я брала інтерв’ю як у звільнених українських військовополонених, так і в російських полонених у українських тюрмах. На основі деяких своїх досліджень я стала співпродюсеркою відзначеного нагородами документального фільму «Під смертельним небом».

Byline Times. Російські воєнні злочини в Україні: тортури як інструмент пропаганди.

Голос Америки. Інтерв’ю з колишніми жертвами російських тортур та тими, хто вижив.

8. Чи можете ви розповісти про Херсон? Яким це місто було до повномасштабного вторгнення і яким є зараз?

Я ніколи не була в Херсоні до його звільнення. Я опублікувала декілька інтерв’ю з людьми, які тоді втекли з Херсона, але ніколи не бачила мирного Херсона. Коли я вперше приїхала, місто було майже неушкодженим – лише де-не-де кілька зруйнованих будівель. За два роки мого життя тут я бачила, як центральна частина Херсона руйнується і перетворюється на порожнечу як Прип’ять або місто-привид на трасі 66 в Америці. Щодня я бачу дедалі більше зруйнованих будівель, попри те що херсонці намагаються прибирати вулиці після кожного обстрілу, садити квіти й навіть прикрашати місто. Щоразу, коли росіяни завдають ударів, українці відновлюють його, але на цей момент це – нерівна боротьба. Відновлення під артилерійським вогнем, авіабомбами та дронами неможливе. Фасад облдержадміністрації, зруйнований росіянами, став символом їхнього варварства. Він стоїть там, на площі Свободи, як свідок злочинів.

Що саме в місті та його мешканцях надихає вас повертатися туди знову і знову та розповідати більше історії про звірства, які росіяни там роблять?

Любов до життя. Квітучі трояндові сади перед руїнами. Кавуни та гарбузи біля уламків будівель. Помідори та соняшники, що ростуть на тимчасових бомбосховищах. Піддони з водою та крихти хліба, розкладені для голубів на вулицях. Сортування сміття під обстрілом. Старі та молоді люди, які займаються спортом у парках під звуки вибухів. Студії боксу, танців та йоги, які процвітають, навіть якщо не всі можуть відвідувати заняття через дрон, що кружляє над ними. Театральні прем’єри, читання поезії, музичні концерти та виставки мистецтва в підвалах. Бібліотеки та книжкові клуби, що відкриваються і проводять майстер-класи під час повітряних атак. Алеї та бульвари, що вишикувалися за подряпаними осколками платанами, вулиці, а восени вони вкриті помаранчевим листям, навіть якщо під листям ховаються протипіхотні міни. Сонячне світло, що грає на розвалених стінах і балконах. Річка, що виблискує так близько і так недосяжно. Звуки цикад влітку вночі. Їх переривають «шахеди». Моя маленька крамничка на розі, де продавчиня знається на політиці краще, ніж більшість аналітиків, в яких я брала інтерв’ю. Великий модний продуктовий магазин із пітахаєю, копченим тофу, комбучею, власною пекарнею з найкращим у світі гарячим житнім хлібом, зі стінами, які прикрашають картини місцевих примітивістських художників. Все – це справжнє.

9. Які речі ви робите лише для себе?

Йога, походи в сауну з подругами, прогулянки, іноді танці. Не вистачає часу, щоб робити все, що я хочу.

Чи можливо залишатися при здоровому глузді під час війни?

Не думаю.

Які речі допомагають вам не втратити себе?

Хто сказав, що я не втратила? Важка атлетика, йога. Макіяж – це трохи медитація, яка заспокоює мої нерви, ритуал, коли ти зосереджена на собі.

10. Чи відчуваєте ви, що війна змінила вас? Як саме?

Так. Я люблю проводити більше часу наодинці. Я ніколи не любила гучних звуків, але тепер я справді чутлива до них. Важко сказати, що ще…

Від початку війни чи щось вас здивувало:

у собі (як ви справлялися з емоціями, залишилися сильним, знайшли натхнення в несподіваних джерелах тощо)? Я не дуже зосереджена на собі, тому важко сказати. Я гадаю, що те, що я роблю, є правильним, тому це може бути дивно. Це не те, що я планувала.

щодо своєї країни? Так, країна, де я народилася (Росія), збожеволіла і стала фашистською. Це дійсно розбило мені серце. Я справді вірила в Америку і любила її. Досі люблю, але це стає все важче. Я навіть не впевнена, чи я маю країну. Україна – це земля моїх предків, і вона стає моїм домом. Хоча я поки не можу назвати її своєю країною.

про ваші уявлення щодо людства? Раніше я не мала ілюзій щодо людства, але війна зробила його справді чорно-білим і суворим. Я бачила жахливі речі, але також бачила багато благородних і дивовижних речей.

Якими були ваші прозріння?

Я думаю, що я не в тому становищі, щоб робити висновки або мати розумові здібності для того, щоб все підсумувати. Я перебуваю в епіцентрі «дій», коли російські дрони декілька разів на день скидають вибухівку біля мого вікна. Лише кілька годин тому на передмістя Херсона було скинуто чотири керовані бомби. Доки вони не впали, ми не знали, куди вони влучать, це могло бути будь-де. Отже, ти просто йдеш вулицею, цікаво, чи не спостерігають за тобою зверху і чи не помреш ти сьогодні. Або ти лягаєш спати і не знаєш, чи прокинешся, тому що надворі вибухи. Щоночі. Гадаю, це прозріння: будь-яка безпека – це ілюзія, а життя жахливо крихке і може закінчитися будь-якої миті, тому я маю прожити, наскільки це можливо, повноцінно цей момент. Не залишати його на завтра. Завтра не слід сприймати як належне. Насправді завтра – це подарунок (не хочу звучати як печиво з передбаченням).

11. Що ви хочете, щоб світ знав про українців у цей момент? Про українських жінок?

Українці – не є жертвами. Україна цінує свободу і волю понад усе. Це глибоко відгукується мені: так само як я відмовляюся ідентифікувати себе, як та що народилася в СРСР, Україна бореться за свою ідентичність поза межами ментальних рамок пострадянського простору. (Можливо, тут варто поставити запитання про моє місце народження.)

Українські жінки – сильні та красиві. Мені не вистачає слів, щоб описати їхню силу духу та тіла. Вони також дуже спортивні та мають міцне тіло. Я також ціную їхню гідність та елегантність, а також увагу до деталей у зовнішньому вигляді. У Херсоні ніхто не ходить неохайним, незважаючи ні на що. Краса проти варварства.

12. Хто з WOW-жінок надихає вас найбільше?

Зараз я читаю книгу про американських жінок-кореспонденток під час Першої світової війни і їхній досвід і твори надихають мене. Наприклад, Неллі Блай. Те саме можна сказати про жінок військових журналісток під час Другої світової війни, таких як Лі Міллер – одна з моїх головних натхненниць. Мої подруги зі студії йоги та танців у Херсоні надихають мене щодня. Вони душевні, сильні, добрі та завжди веселі, хоча вони пережили та продовжують переживати пекло. Наприклад, танцівниця з мого фільму Альона – така багатогранна, талановита, працьовита, а також скромна.

13. На вашу думку, чим росіяни відрізняються від українців?

Різна історія, різний національний характер. Росіяни завжди жили в різних формах кріпацтва. Свобода і вільна воля для них – порожні слова. Українці не просто вірять у свободу – вони її втілюють і живуть нею. Україну визначає вільний вибір. Гасло «Немає долі» на останньому фестивалі «Burning Man» є хорошим прикладом цього. Українці також дуже працьовиті, на відміну від росіян, які схильні до привласнення. І українці надзвичайно охайні. Я маю на увазі вулиці, будинки і навіть окопи. Інший рівень життя.

Звісно, це в загальному, я знаю лінивих і фаталістичних українців, а також у своєму житті зустрічала кількох росіян, які померли за свободу. Як я вже казала, людину не визначають обставини народження. Є свобода вибору.

Ви хочете справедливості для росіян? Ви вважаєте це можливим? Що б ви хотіли побачити?

Так. Я вірю в колективну відповідальність. Я хочу трибуналів і судів. Сподіваюся, що мої звіти будуть використані як докази. Я вірю, що все можливо. Нам просто потрібно наполегливо працювати і домогтися цього.

14. Як ви бачите динаміку змін всередині країни, ставлення до тих, хто виїхав, і тих, хто залишився? Чи вважаєте ви, що українці, які виїхали з країни, мають особливу відповідальність перед своєю Батьківщиною?

Я бачу різні ставлення; це дійсно залежить від людини. І від регіону. У Херсоні я відчуваю, що люди все більше і більше втомлюються від жахіть, які на них звалилися, і, як результат, вони втрачають толерантність чи терпіння до тих, хто виїхав і не допомагає. Однак я не можу говорити за інших людей. Можу сказати, що під час моїх останніх візитів я була дуже засмучена ставленням деяких українців у США та Європі, яке варіювалося від байдужості до відкритої ворожості та відмови допомагати Україні. Однак я не маю права судити. Я лише фіксую.

15. Яке місце або заняття дозволяє вам почуватися найщасливішою?

Зараз? Йога-студія тут і прогулянки вулицями старого Херсона.

16. Що ви зробите в першу чергу, коли Україна переможе?

Я вип’ю шампанське з Бахмута з найближчими друзями в Одесі. Ми вже давно цього чекаємо. А ще піду танцювати і в Одесі, і в Херсоні.

Які мрії ви маєте для себе та своєї родини після закінчення війни?

Я хочу поїхати до Австралії та дослідити фольклор аборигенів. Також я хочу поїхати на Мадагаскар і побачити всіх тварин, які там живуть. Я хочу погуляти на пляжі Ланжерона в Одесі, їсти вишні, пити коктейлі і читати романи. Я хочу прогулятися до Дніпра в Херсоні і доторкнутися до води – за три роки, що я тут живу, я не мала такої можливості. Я хочу побачити лівий берег у всій його красі. Я хочу поїхати в український Крим! Боже, скільки ж я хочу зробити!

17. Де інші можуть знайти вас/ваші роботи? (посилання на вебсайт, блог тощо).

Ви можете переглянути мій документальний фільм на www.khersonhumansafari.com. Я є військовою кореспонденткою Byline Times, Euromaidan Press, Fresno Alliance, а також пишу і роблю репортажі для інших видань, зокрема BBC Radio. Я щодня публікую посилання на свої роботи та звіти в соціальних мережах: X @ZarinaZabrisky, Instagram, FB, Bluesky, YouTube. Багато моїх статей, написаних до початку повномасштабного вторгнення, можна знайти на Medium.